Scientific and Technological Research Article

Creation of a techno-pedagogical model for the strengthening of the Emberá Katío language through ancestral customs at the El Rosario educational institution in Tierralta

Creación de un modelo tecno-pedagógico para el fortalecimiento de la lengua Emberá Katío mediante las costumbres ancestrales en la institución educativa el Rosario de Tierralta

Mariano Esteban Romero Torres1 ![]() *, Pedro Gamero De La Espriella1

*, Pedro Gamero De La Espriella1 ![]() *

*

ABSTRACT

The reduction in the number of native speakers of a language presents a significant blow to the intangible heritage of nations, territories, and regions. Its preservation and conservation hinge on a broad array of factors, with education playing an integral role. The research presented here aimed to model the strengthening of the Emberá Katío language within the El Rosario Educational Institution in Tierralta, Córdoba, from a techno-pedagogical perspective. Its primary objective was to help mitigate the loss of linguistic and cultural identity associated with this native and ancestral language. Using an action-research methodology, the study sought to lessen the impact of conventional western teaching-learning methods that harm the Emberá Katío language. The research designed alternatives for cultural preservation, employing systems within the classroom setting, with a research-focused and ethno-educational methodological approach. Fieldwork was included to facilitate student interaction with community knowledge bearers, and to collect, organize, and evaluate information. The results enabled the generation of a collaborative document that will serve as a pedagogical tool for future generations of students.

Keywords: rural education, mother tongue instruction, social studies, cultural minority.

JEL Classification: I29; Z19

RESUMEN

La disminución del número de hablantes nativos de una lengua, representa un duro golpe para el patrimonio intangible de naciones, territorios y regiones. Su salvaguarda y conservación están sujetos a una amplia diversidad de factores, dentro de los cuales la educación juega un papel fundamental. La investigación que se presenta estuvo dirigida a modelar, desde la tecno-pedagogía, el fortalecimiento de la lengua Emberá Katío, en la Institución Educativa El Rosario, de Tierralta, Córdoba. Su propósito fundamental fue contribuir a mitigar la pérdida de la identidad lingüística y cultural asociadas a esta lengua nativa y ancestral. A partir de una metodología investigación-acción, se persiguió atenuar la inmersión de métodos convencionales de enseñanza – aprendizaje de origen occidental, en detrimento de la lengua Emberá Katío. Se diseñaron alternativas dirigidas el rescate cultural, mediante el uso de sistemas al interior del aula de clases, con un enfoque metodológico investigativo y etnoeducativo. Se incluyó el trabajo de campo para promover la interacción de los estudiantes, con sabedores comunitarios y la recopilación, organización y evaluación de la información. Los resultados obtenidos permitieron generar un documento conjunto, que sirve como herramienta pedagógica en el futuro para nuevas generaciones de estudiantes.

Palabras clave: educación rural, enseñanza de la lengua materna, estudios sociales, minoría cultural.

Clasificación JEL: I29; Z19

Received: 17-03-2023 Revised: 23-05-2023 Accepted: 15-06-2023 Published: 04-07-2023

Editor: Carlos Alberto Gómez Cano ![]()

1Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia. Bogotá, Colombia.

Cite as: Romero, M. y Gamero, P. (2023). Creación de un modelo tecno-pedagógico para el fortalecimiento de la lengua Emberá Katío mediante las costumbres ancestrales en la institución educativa el Rosario de Tierralta. Región Científica, 2(2), 202398. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202398

INTRODUCTION

Language has a fundamental relevance for the culture and identity of a people or region (Brisset et al., 2021). The practices, knowledge, and worldviews crystallized in language are essential sources for cultural transfer and social development as a system (Tom et al., 2019). Due to their common representation as minorities and the loss of space in decision-making, indigenous cultures have suffered from marginalization, precariousness, and limitations to maintain the sustainability of their educational systems (Tom et al., 2019). As language is a process in close unity with thought, the identity of these peoples suffers from the infiltration and cultural appropriation of globalization, which threatens the social reproduction of their ancestral customs. Therefore, applying basic pedagogical principles is a success factor in blended or blended learning models (Bizami et al., 2023).

Aspects such as biodiversity protection, cultivation, and harvesting have been linked to the development of regions, not only historically, but as possible contributors to sustainability policies (Zabel et al., 2019). However, the colonial influence, the Eurocentrism of the modern project of society, and the curriculum design under these precepts have had a substantial impact on the pedagogy and socioeconomic life of these peoples (Shahjahan et al., 2021; Valencia et al., 2017).

In the case of the native peoples of South America, for more than 500 years, their daily life was based on solid worldviews and culture. The process of colonization, importation, and cultural imposition caused the disappearance of their culture in numerous ethnic groups and native peoples due to the inability to transfer. In the meantime, critical aspects of humanity's heritage, such as history, identity, and spiritual constructions, were lost.

Even those who have managed to keep their customs alive through oral transmission and practice are now affected in their educational processes. Today, the loss and deterioration of the identity of the native and ancestral language of the indigenous people within the Emberá Katío culture is evident. The initial diagnoses carried out point, at least in the pedagogical dimension, to introducing conventional teaching methods subordinated to the globalized culture. Financial dependence and the acceptance and implementation of public policies act negatively from a social point of view. These factors do not contribute to the visibility and sustainability of the life systems of this culture. The cultural, educational, and social practices imposed from outside do not promote the sense of life, the internal socio-historical dynamics, and the processes of this indigenous community.

This problematic situation is configured in such a way that the form and lifestyle of native cultures are fragmented to the depths of the cosmology and experience of indigenous peoples. Introducing new technologies is seen as an opportunity to strengthen the Embera language. Another fundamental aspect highlighted in the scientific literature is educational leadership and its link with new technologies (Hallinger, 2020; Laufer et al., 2021). In this sense, supporting the different rescue plans carried out by the Ministry of the Interior is necessary. Especially those presented to contribute to the recovery of the ancestral language so that the learning and practice of all those traditional and cultural factors that constitute the wealth of each indigenous people benefit.

In response to the loss of the cultural identity of the native language in the region's educational institutions, new technologies are being used to rescue the ancestral language and the historical memory lost through family and community teaching. This effort is oriented to a resurgence in the classroom, with new teaching-learning methods, but from an ethno-educational, multicultural, and pluricultural approach. The following research question arose based on the problems above How to strengthen the Emberá Katío language by re-signifying ancestral customs in the El Rosario Educational Institution of Tierralta, Córdoba?

Consequently, the specific objectives included the identification of the customs and traditions of the Emberá Katío indigenous reserves located in the municipality of Tierralta. The cultural traits of the Emberá Katío, both preserved and extinct, were determined within the population of the Tierralta reservation. Subsequently, a teaching model was developed, mediated by technology and containing didactic contents related to the customs and traditions of the Emberá Katío indigenous reservations, for its implementation in the El Rosario Educational Institution.

METHODS

Approach and design

The research was based on a qualitative methodological approach. As Hernández and Mendoza (2018) call it, the qualitative route is characterized by the author's interest in fundamentally understanding the phenomenon under investigation from the perspective of the subjects participating in the research. The approach adopted was inductive and ecological, focused on the participants' and researchers' representations, beliefs, and attitudes concerning the research object, which corresponds to the methodological scaffolding of qualitative research (Taylor et al., 2016).

A defining element incorporated into the research design was its transformative and participatory community outreach. This type of approach, called community-based participatory research (CBPR), according to Leavy (2017), is based on the conformation of work teams between researchers, community agents, subjects of the processes, and stakeholders. This is to execute a research design to solve a common problem (Leavy, 2017).

In socio-educational research, Johnson and Christensen (2019) call this type of research action-research since it is based on a combination of both to generate knowledge and solutions to problems of practice that generally transform. According to the authors above, this approach requires a specific attitude that allows thinking like a professional in the field and creating better strategies to improve the research environment or context.

The design implementation results were evaluated by analyzing qualitative data from the researchers' field log, the interviews of key participants, and the products of the research activity. The qualitative sample, which is characterized by not being homogeneous or statistically selected, was made up of 30 students from the El Rosario Educational Institution in Tierralta, Córdoba, five community agents representing the Emberá Katío culture, and three gatekeepers identified as community leaders.

The first step in the construction of the research was the sensitization of students regarding the preservation needs of the ancestral cultural heritage of the Emberá Katío people. According to Leavy (2017), in addition to integrating the different agents and members of a research and participation team, it is necessary to incorporate agents of change and leaders in the community. Therefore, during this first phase, we sought to promote student leadership and researchers' approach to the context's active members.

Another critical result in this first phase was the constitution of groups for organizing the participants. Based on the recommendations of Leavy (2017), an advisory board composed of students and community members was created. In addition, a research board and another were created to execute the actions. These boards were at no time composed of the same staff, at least as far as students were concerned, as a democratic decision-making process representative of the debate, experiences, and ideas of the members was pursued.

Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of the distribution of leadership in formative contexts (Azorín et al., 2019; García, 2019; Harris et al., 2022). In preserving tangible and intangible cultural aspects, this distribution of actions, knowledge, and active participation plays an essential role. In this sense, in this first phase, brief talks were given on the Emberá Katío culture and language and the importance of its preservation. Other studies have emphasized the importance of this prior preparation, both for forming distributed leadership and achieving the intervention's target system (Lumby, 2019; Rodríguez et al., 2023; 2023b; Yan et al., 2020).

This initial preparation of the students allowed them to think about a techno-pedagogical model that would allow the strengthening of the Emberá Katío language. Additionally, it did not situate them as objects of a pedagogical experiment or as students receiving a subject. This approach has been successfully employed in previous studies, where the importance of avoiding skepticism toward the pedagogical use of technologies is recognized (Zaimakis & Papadaki, 2022). Gradually, students began to incorporate into their behavior the role of transforming the researcher of the context. This action was initially problematic since - according to some of the key participants interviewed - it implied a responsibility to which they were not accustomed.

One of the main lines of work, the integration of ancestral customs into educational practices at the El Rosario Educational Institution in Tierralta, Córdoba, was especially problematic, as it involved the transformation not only of the teaching content but also of the methods, which required adaptations for its implementation. In this state, it was a priority to think collectively and distribute tasks for the design of a dynamic model of relationship management between students, teachers, ancestors, territory, and technology, which -by nature- was responsive to the needs of each group of key participants. It was challenging that this design would allow for innovative education and directly impact the strengthening of the Katio language.

One of the main intentions was to incorporate technologies for training, as several studies have shown the importance of social networks as a space for the exercise of leadership (Daly et al., 2019; Laufer et al., 2021). For this purpose, measures were considered to reduce the risks of addiction, procrastination, and violence, among others, considered as the main negative factors associated with the use of social networks (Cebollero et al., 2022; Suárez et al., 2022). In this sense, the design of an online educational model with massive and open access was proposed. This first proposal represented an opportunity to analyze the implications of open access, cultural appropriation, globalization, and other critical aspects of cultural preservation.

Although some of these topics had been previously introduced in the preparation, their discussion as an integrated system of knowledge and practices suggested that it was beyond the epistemological possibilities of the students. Other studies suggest that distributed leadership training (Rodríguez et al., 2023) and social networks (Misas et al., 2022) can motivate student behavior changes. Therefore, it was concluded that such a process was gradual and individual, so that it may represent a challenge for subjects and their groups.

The main achievement was projecting the democratic and participatory style of the primary research approach in developing the model. This led to a flexible learning modality designed so that students can access the contents from wherever they are and in the available space. This asynchronous approach, which is effectively valued as positive, favors, above all, to cover the topics at their own pace (Reed et al., 2023; Varkey et al., 2022; Wegener, 2022). One aspect that researchers emphasized and was incorporated into their work by the boards was to go beyond instruction as the core of the techno-pedagogical model since, according to studies consulted, for some circles, techno-pedagogy means exclusively conferencing on devices linked to the Internet (Gurukkal, 2021).

From this perspective, the model was conceived as a guide for pedagogical action aimed at preserving the customs and traditions of the culture of the Emberá Katío indigenous reservations located in the municipality of Tierra Alta, Córdoba. Therefore, it was conceived and represented by the participants as a tool that allows the development of educational processes so that planning, management, organization, and control would be a fundamental basis in the integration of ICT within the functioning of the institution. The main contribution of the research in this aspect was that, in addition to favoring the integration of ICT from the teachers' actions, it incorporated the students' collaborative design. This was a need evaluated as unmet in the scientific literature (Gómez et al., 2022; Lawrence et al., 2020).

This model was developed to enable the generation of profiles of students entering the open and distance learning platforms, which facilitates the evaluation of various factors associated with the success of its implementation. According to interviewees and researcher notes, it was ideal for both current users and future generations to know demographics, personal, social, and educational needs, future aspirations and cognitive interests, and group and organizational climate. About research conducted with a similar approach to this study, it is vital to achieve unity among these factors for each educational agent involved in transforming the educational reality. Studies suggest, mainly, that these programs and strategies should be conducted to promote the students' life project through their socio-educational inclusion and future careers (Garcés et al., 2022; 2020; Pérez et al., 2023; Santana et al., 2019).

In the final phase of the research, the participants evaluated the experience as a whole. The following were evaluated: the initial state of the problem, the process, and the progress, an aspect that allowed the construction of a group evaluation, which was explored through interviews with key participants. The main results pointed out that the model would help avoid student desertion and create a sense of belonging to the institution based on considering the subjects as essential. The practical results showed that the number of people in the region with native language proficiency increased.

It should be noted that the number of student dropouts and their psychosocial impact were reduced. According to studies consulted for a better understanding of the results achieved, when a student drops out, in general, he/she does not manage to resume his/her studies successfully; it generates disappointment and negative emotions in the person, the family, and the context, which conditions the student's life project (Garcés et al., 2020). With this online educational model, with massive and open access, the El Rosario Educational Institution of Tierralta, Córdoba, can offer quality content to a large number of students, not only in the region but throughout the territory where the descendants of the Embera Katio culture are located.

In this way, it contributes to preserving the culture and legacy since those who wish to do so have the opportunity to study and acquire the proposed competencies. This aspect resulted from the joint decision-making process. This led to recognizing the need to train and develop socioemotional and professional competencies. This result arises from not focusing the model exclusively on the performance of a task but on human welfare, future job opportunities, and the cultural value of learning about the cultural aspects preserved. Finally, it is necessary to mention the importance of educational quality assessment processes. Rather than establishing a design that considers quality as a factor or quality inherent to the service itself, it was advocated that the student should be the one to evaluate it according to the context.

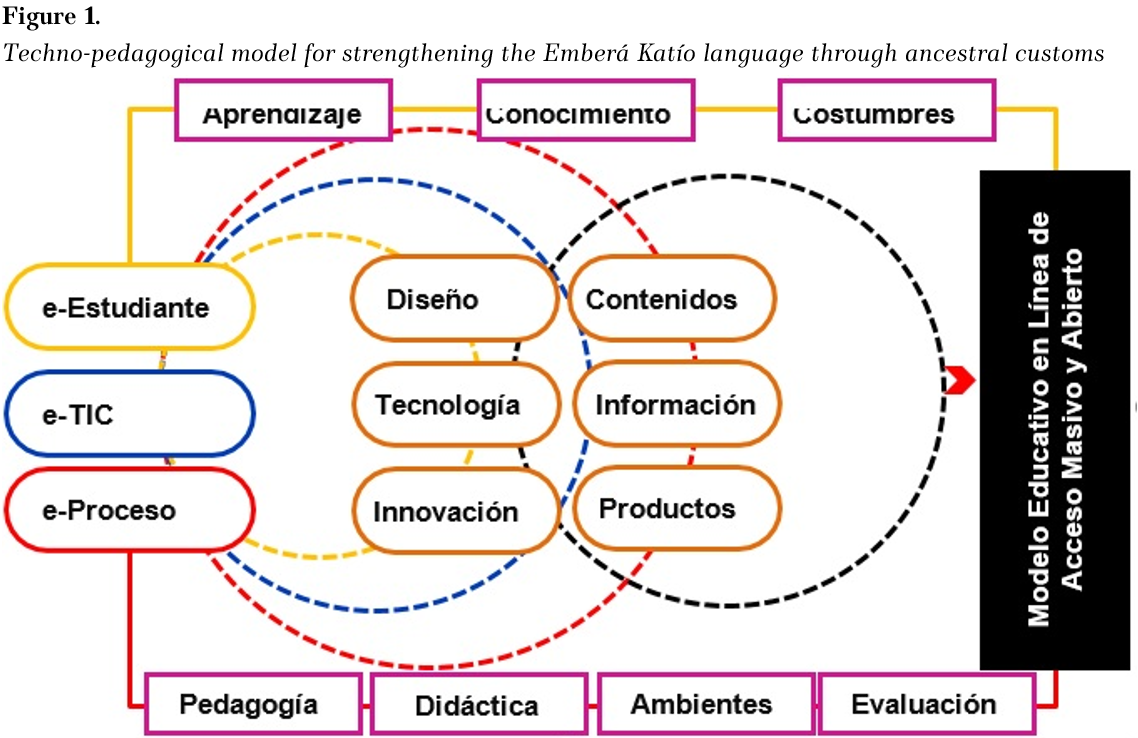

The evaluation of the progress made showed that the indicators that allow evaluating the perceived quality and the satisfaction of the users were rated as high. Projectively, it is considered that this model will favor the social reproduction, transfer, and conservation of the Emberá Katío language. Additionally, the model should be established as competitive in the educational sector for the educational institution to reach high levels of reliability, credibility, and strength, where students are kept motivated in each of the activities of the educational process. Its final configuration and representation can be seen in figure 1.

Source: own elaboration.

Note: the figure appears in its original language.

As can be seen, the final construction of the study, at least up to the moment of presentation of this text, offers a broad platform for all the factors involved in techno-pedagogy. In addition, it is accompanied by the report to the institution, consisting of the main results achieved in the study, the assessments of the key participants, and the interpretation of the researchers.

CONCLUSIONS

The modeling of the strengthening of the Emberá Katío language, through the precepts of techno-pedagogy, contributes to preserving the ancestral customs in the Educational Institution El Rosario of Tierralta, Córdoba. In addition, it allows for establishing the guidelines to maintain a quality educational process, preserving the native and ancestral features of the Emberá Katío language as a characteristic attribute of the territory.

It is concluded that it is necessary to generate accessible conditions for the emergence of new methods that contribute to the growth of ideas in favor of developing the communities with their identities in the face of a changing society and the technological world. With this in mind, participatory, democratic, and distributed approaches to leadership can offer a significant conceptual and practical framework.

REFERENCES

Azorín, C., Harris, A. y Jones, M. (2019). Taking a distributed perspective on leading professional learning networks. School Leadership & Management, 40(2-3), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1647418

Bizami, N., Tasir, Z. y Na, K. (2023). Innovative pedagogical principles and technological tools capabilities for immersive blended learning: a systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 28(2), 1373–1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11243-w

Brisset, A., Gill, R. y Gannon, R. (2021). The search for a native language: Translation and cultural identity. In The translation studies reader (pp. 289-319). Taylor & Francis.

Cebollero, A., Cano, J. y Orejudo, S. (2022). Are emotional e-competencies a protective factor against habitual digital behaviors (media multitasking, cybergossip, phubbing) in Spanish students of secondary education? Computers & Education, 181, 104464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104464

Daly, A., Liou, Y., Del Fresno, M., Rehm, M. y Bjorklund, P. (2019). Educational Leadership in the Twitterverse: Social Media, Social Networks, and the New Social Continuum. Teachers College Record, 121(14), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811912101404

Garcés, Y., Santana, L. y Feliciano, L. (2020). Proyectos de vida en adolescentes en riesgo de exclusión social. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 38(1), 149-165. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.332231

Garcés, Y., Santana, L., y Feliciano, L. (2022). Desarrollo emocional y contexto sociofamiliar en adolescentes en riesgo de exclusión. REIDOCREA, 11(28), 329-339. https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/76061

García, D. (2019). Distributed leadership, professional collaboration, and teachers’ job. Teaching and Teacher Education, 79, 111-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.12.001

Gómez, F., Trespalacios, J., Hsu, Y. y Yang, D. (2022). Exploring Teachers’ Technology Integration Self-Efficacy through the 2017 ISTE Standards. TechTrends, 66, 159-171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00639-z

Gurukkal, R. (2021). Techno-Pedagogy Needs Mavericks. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 7-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631121989478

Hallinger, P. (2020). Science mapping the knowledge base on educational leadership and management from the emerging regions of Asia, Africa and Latin America, 1965–2018. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 48(2), 209-230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143218822772

Harris, A., Jones, M. e Ismail, N. (2022). Distributed leadership: taking a retrospective and contemporary view of the evidence base. School Leadership & Management, 42(5), 438-456. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2022.2109620

Hernández Sampieri, R., y Mendoza Torres, C. (2018). Metodología de la Investigación: Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta (1ra ed.). McGraw-Hill Interamericana.

Johnson, R. y Christensen, L. (2019). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Sage Publications.

Laufer, M., Leiser, A., Deacon, B., Perrin de Brichambaut, P., Fecher, B., Kobsda, C. y Hesse, F. (2021). Digital higher education: a divider or bridge builder? Leadership perspectives on edtech in a COVID-19 reality. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00287-6

Lawrence, G., Ahmed, F., Cole, C. y Pierre, K. (2020). Not more technology but more effective technology: Examining the state of technology integration in EAP programmes. RELC Journal, 51(1), 101-116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220907199

Leavy, P. (2017). Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches. The Guilford Press.

Lumby, J. (2019). Distributed Leadership and bureaucracy. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 47(1), 5-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217711190

Misas, J., López, M. y Marichal, O. (2022). Las redes sociales como espacio de formación de líderes juveniles. Revista Conrado, 18(88), 375-383. https://conrado.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/conrado/article/view/2614/2538

Pérez, A., García, Y., García, J. y Raga, L. (2023). La configuración de proyectos de vida desarrolladores: Un programa para su atención psicopedagógica. Revista Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 23(1), 1-35. https://doi.org/10.15517/aie.v23i1.50678

Reed, J., Kopot, C. y Medvedev, K. (2023). Student perceptions of asynchronous learning in an introductory online fashion course. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 16(1), 79-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2022.2124313

Rodríguez, E., Pérez, A. y Camejo, Y. (2023). Formación del liderazgo distribuido en los estudiantes de la carrera Gestión Sociocultural para el Desarrollo. Atenas, 61, 1-13. http://atenas.umcc.cu/index.php/atenas/article/view/778

Rodríguez, E., Pérez, A. y Camejo, Y. (2023). La formación del liderazgo distribuido en la intervención a favor del patrimonio cultural. Transformación, 19(2), 240-255. https://revistas.reduc.edu.cu/index.php/transformacion/article/view/e4313

Santana, L., Medina, P. y Feliciano, L. (2019). Proyecto de vida y toma de decisiones del alumnado de Formación Profesional. Revista Complutense de Educación, 30(2), 423-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/RCED.57589

Shahjahan, R., Estera, A., Surla, K. y Edwards, K. (2021). “Decolonizing” Curriculum and Pedagogy: A Comparative Review Across Disciplines and Global Higher Education Contexts. Review of Educational Research, 92(1), 73-113. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211042423

Suárez, A., Ruiz, Z. y Garcés, Y. (2022). Profiles of undergraduates’ networks addiction: Difference in academic procrastination and performance. Computers & Education, 181, 104459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104459

Taylor, S., Bogdan, R. y DeVault, M. (2016). Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: a guide book and resource. Wiley.

Tom, M., Huaman, E. y McCarty, T. (2019). Indigenous knowledges as vital contributions to sustainability. International Review of Education, 65, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-019-09770-9

Valencia, J., Muñoz, E. y Hainsfurth, J. (2017). El extractivismo minero a gran escala. Una amenaza neocolonial frente a la pervivencia del pueblo Embera. Luna Azul, 45, 419–445. https://doi.org/10.17151/luaz.2017.45.21

Varkey, T., Varkey, J., Ding, J., Varkey, P., Zeitler, C., Nguyen, A., . . ., y Thomas, C. (2022). Asynchronous learning: a general review of best practices for the 21st century. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 16(1), 4-16. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-06-2022-0036

Wegener, D. (2022). Information Literacy: Making Asynchronous Learning More Effective With Best Practices That Include Humor. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48(1), 102482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102482

Yan, L., Bellibaş, M. y Gümüş, S. (2020). The effect of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Mediating roles of supportive school culture and teacher collaboration. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(3), 430-453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220910438

Zabel, F., Delzeit, R., Schneider, J., Seppelt, R., Mauser, W. y Václavík, T. (2019). Global impacts of future cropland expansion and intensification on agricultural markets and biodiversity. Nature Communications, 10, 2844. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10775-z

Zaimakis, Y. y Papadaki, M. (2022). On the digitalisation of higher education in times of the pandemic crisis: techno-philic and techno-sceptic attitudes of social science students in Crete (Greece). SN Social Sciences, 2(6), 77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00380-1

FINANCING

No external financing.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (ORIGINAL SPANISH VERSION)

Se agradece a la Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia (UNAD) por el apoyo recibido para el desarrollo de la investigación.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Mariano Esteban Romero Torres and Pedro Gamero De La Espriella.

Research: Mariano Esteban Romero Torres and Pedro Gamero De La Espriella.

Methodology: Mariano Esteban Romero Torres and Pedro Gamero De La Espriella.

Validation: Mariano Esteban Romero Torres and Pedro Gamero De La Espriella.

Writing - original draft: Mariano Esteban Romero Torres and Pedro Gamero De La Espriella.

Writing - revision and editing: Mariano Esteban Romero Torres and Pedro Gamero De La Espriella.