doi: 10.58763/rc2025484

Review Article

The community residing in urban public spaces and their heritage

La comunidad residente en los espacios públicos urbanos y su patrimonio

Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez1 ![]() *, José Manuel Hernández

de la Cruz2

*, José Manuel Hernández

de la Cruz2 ![]() *, Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante1

*, Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante1 ![]() *

*

ABSTRACT

Introduction: this article aimed to explore the relationship between the inhabitants of public spaces from a sociocultural and heritage perspective.

Methodology: this research was conducted from a qualitative perspective. Using a documentary review approach, the main categories in high-impact databases were analyzed between 2020 and 2025.

Results: by applying methods and techniques specific to this methodological perspective, it was possible to identify how resident communities consciously appropriate their heritage and enable the conservation of these spaces, while transforming them into scenarios of collective identity, confluence, and social memory. The results indicate the existence of some cultural practices associated with their inappropriate use and management strategies that do not promote sustainability.

Discussion: the study highlights the importance of community integration in urban planning, while promoting a participatory approach to ensure heritage preservation and social cohesion.

Conclusion: it concludes that these urban spaces are not only physical spaces, they are repositories of cultural meanings and the community’s own memory, which require protection and revitalization for future generations.

Keywords: historic center, community, urban development, community participation, cultural heritage.

JEL Classification: I38, R00, R38

RESUMEN

Introducción: el presente artículo tuvo como objetivo explorar la relación entre los habitantes de los espacios públicos desde una perspectiva sociocultural y patrimonial.

Metodología: esta investigación se realizó desde una perspectiva cualitativa. Bajo un enfoque de revisión documental, se analizaron las categorías principales en bases de datos de alto impacto entre los años 2020 y 2025.

Resultados: a partir de la aplicación de métodos y técnicas propios de esta perspectiva metodológica, se pudo identificar cómo las comunidades residentes se apropian de su patrimonio de forma consciente y permiten la conservación de estos espacios, a la vez que los transforman en escenarios de identidad colectiva, confluencia y memoria social. Los resultados indican la existencia de algunas prácticas culturales asociadas a su uso inadecuado y estrategias de gestión que no fomentan la sostenibilidad.

Discusión: en el estudio se destaca la importancia de la integración comunitaria en la planificación urbana, a la vez que se promueve un enfoque participativo para garantizar la preservación del patrimonio y la cohesión social.

Conclusión: se concluye que estos espacios urbanos no son únicamente espacios físicos, sino depositarios de significados culturales y la propia memoria de la comunidad, los cuales requieren ser protegidos y dinamizados para las futuras generaciones.

Palabras clave: centro histórico, comunidad, desarrollo urbano, participación comunitaria, patrimonio cultural.

Clasificación JEL: I38, R00, R38

Received: 15-03-2025 Revised: 30-06-2025 Accepted: 18-06-20253 Published: 31-07-2025

Editor:

Alfredo Javier Pérez Gamboa ![]()

1Universidad de Matanzas. Matanzas, Cuba.

2Universidad de Zaragoza. Zaragoza, España.

Cite as: Jiménez Pérez, G. A., Hernández de la Cruz, J. M. y Peñate Villasante A. G. (2025). La comuni-dad residente en los espacios públicos urbanos y su patrimonio. Región Científica, 4(2), 2025484. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2025484

INTRODUCTION

Urban public spaces are fundamental settings for the social, cultural, and economic development of communities (Zarie et al., 2024). These spaces emerged from a variety of interests. Since the founding of cities, many of them were conceived for recreational, commercial, religious, and military purposes, among others. These spaces were not limited to squares but currently include parks, avenues, markets, and pedestrian walkways, which serve not only practical functions but also safeguard the meanings, symbols, intangible elements of heritage, and the collective identity of those who inhabit and intervene in them (Bernabeu Bautista et al., 2023).

In recent decades, as a result of urbanization and globalization, these urban public spaces have been transformed, while their use and heritage values have been affected and modified, in addition to changes associated with the dynamics of original urban planning (Jiménez Pérez et al., 2025). This tendency has generated growing academic interest in understanding how communities interrelate with these environments and how governments and other actors can ensure their preservation and sustainability over time. These public spaces can be open or closed, covered or uncovered, with free or limited access, or with admission rights (Pereira & Rebelo, 2024). In the latter case, they do not always meet the characteristics of true public spaces, making it necessary to review the indicators for admission criteria (Peterson, 2024).

In Latin American contexts, urban public spaces have been studied for their role as repositories of social and cultural memory (Vazquez et al., 2024). Experiences in Chile are presented, such as the case of working with older adults in public spaces (Herrmann Lunecke et al., 2024). By this, different investigations have been developed from the urban planning (Gargiulo & Sgambati, 2022), architectural, community (García Mayor et al., 2025), social (Duignan et al., 2023), economic, heritage, tourism, environmental (Ciacci et al., 2023), artistic point of view, among others.

These public spaces are not only places for activities (Blečić et al., 2024); they also constitute important scenarios for resistance, appropriation, and identity construction. Their purpose and values of use and consumption vary depending on the meaning each generation gives them. Many of the studies reviewed identify how their thematic focus is on architectural and urban planning aspects. They do not always consider the sociocultural and heritage perspectives of the resident communities.

In this sense, a comprehensive understanding of how residents interact with spaces and the heritage contained within them is limited (Legg, 2025); in turn, how these interactions influence their configuration. The authors' analysis revealed various theoretical gaps in the literature regarding public policies and urban development projects, in which the resident community is not always taken into account (Wang & Vu, 2023). This situation has negatively impacted the loss of traditions, trades, and other intangible heritage elements that are carried only by those who inhabit them.

In turn, this has influenced the significance and values attributed to buildings and other heritage elements. Also associated with this issue is the fragmentation of the social fabric, which is not always a consequence of the migration of Indigenous communities but rather the lack of interest and inadequate management of these areas by local authorities.

The texts analyzed by the authors were identified in high-impact databases published between 2020 and 2025. They were able to identify the main trends and theoretical gaps in the existing literature. The study also allowed for the construction of a theoretical framework, taking as a reference previous research definitions regarding the categories "urban public spaces," "heritage education," "heritage," "sustainability," "citizen participation," and others.

In addition, specific studies and case studies were considered that reveal positive experiences in the management of urban public spaces. This approach allowed for comparative analyses of the local and global dynamics in these spaces. Overall, this article provided a deeper understanding of the relationship between communities and urban public spaces. It recognizes their heritage value and their role in the construction of collective identities. It also explains how to plan and manage these spaces more inclusively and reasonably. It is important to ensure their sustainability for future generations.

The increasing and rapid urbanization of heritage cities has generated challenges for the preservation of their cultural heritage and its essence. It is common to observe how many cities have transformed their public spaces; in other cases, one can see the interest of institutions and the community itself in rescuing the integrity and originality of these spaces. In many cases, real estate development and modernization have brought with them unfavorable consequences for these public spaces. Their destruction or alteration can be observed in daily life, even when they possess significant historical and symbolic value.

This scenario affects their physical integrity and also erodes the cultural practices, social networks (non-technological), and experiences that develop in public spaces. Therefore, there is a growing need for researchers to study how communities resist, adapt, or accommodate these changes and how these influence the reconfiguration or lack thereof of contemporary urban heritage (Fior et al., 2022).

Globalization, which has introduced new forms of interaction in public spaces, cannot be overlooked in this type of study. Most often, this is associated with the implementation of digital technologies and foreign dynamics that adapt to them (Yang & Zhang, 2024). This knowledge gap generates comparative studies between the local and the global, the traditional and the modern, the representative, the authentic, and the innovative. In this specific case, the present study allows us to identify in the literature how resident communities respond to these aspects and how their social representations and collective identities change in the valuation of heritage.

Furthermore, the lack of active participation of communities in decision-making regarding the use of public spaces is evident. Positive examples can be seen in the popular consultation; however, the lack of community participation is also a recurring problem. Associated with this, specialists with advanced technical skills often develop public policies, but they ignore the evaluative criteria of those who live there, with particular emphasis on the resident community.

On many occasions, it is possible to identify how their needs and expectations are not considered. This disconnect has generated and associated frequent problems, which have led to the ineffectiveness of initiatives established by local institutions and governments. This article identifies the importance of incorporating participatory approaches, in which communities are recognized as key stakeholders in the management of their heritage, especially in urban public spaces.

This study sought to explore the relationship between the resident community and public spaces from a perspective that integrates sociocultural and heritage elements. Also, the research was based on the premise that these urban public spaces are not merely physical settings but are also charged with meanings attributed by visitors and carried by the resident communities. These meanings emerge from the practices, social representations, and traditions of those who inhabit them.

It takes into account that urban public spaces are not static but dynamic and constantly changing; they evolve in response to the needs of the communities that inhabit them. This premise allows us to analyze heritage in constant transformation as a living process that is constructed daily. Furthermore, this study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of public space and its sustainable management in a way that respects its heritage value and functions as a platform for inclusion and social cohesion.

METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted using a qualitative approach. It explored the relationship between the resident community and urban public spaces. Specifically, the Urban Historic Center of the city of Matanzas, Cuba, was used as a reference. The case study method was used to comprehensively analyze a specific context and take into account its historical, cultural, social, and political particularities. This approach allowed for a comprehensive examination of this context, as well as an analysis of local dynamics and the identification of significant patterns in the relationship between residents and their heritage environment.

Document Review

Based on the categories identified in the research, a source analysis was conducted. Initially, a document review was conducted in high-impact databases such as:

· Scopus.

· Web of Science.

· Scielo.

Other sources of interest published in Google Scholar were also consulted.

The inclusion criteria were:

· Database (high-impact and Google Scholar).

· Publication period (2020-2025).

· Appropriateness of the research topic (title, abstract, results).

· Language (Spanish or English).

· Area of knowledge (Sociology, Demography, Psychology, Urban Planning).

In this case, studies on the topic published between 2020 and 2025 were identified that met the search strategy, which was based on Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and terms such as "urban public spaces," "cultural heritage," "resident community," and "participation."

This allowed for the construction of the theoretical framework, the identification of definitions for this category, and the main trends and experiences. The research team also consulted specific documents on the Urban Historic Center of the city of Matanzas. These include the National Monument Declaration File, management plans for the historic center, the Strategic Plan for the Comprehensive Development of the city, government reports, and scientific publications that address this context.

Case Study

Once the authors completed the analysis and literature review, the instruments for data collection and processing were designed:

· Semi-structured interview guide.

· Participant observation guide.

· Focus group discussions.

It was necessary to identify key informants for the consultations. Semi-structured interviews were designed for specialists in the field, teachers, and researchers closely related to these aspects. In addition, a participant observation guide was designed to determine how the interaction between the community and public spaces is established. Two focus groups were held: one composed of technicians and directors of heritage institutions, and the second of these composed of sociocultural managers, social actors, non-state economic actors, and directors of institutions located in urban public spaces in the city of Matanzas or its immediate surroundings.

The main aspects addressed in the designed instruments

The interviews explored the leading practical positions and assessments of specialists regarding public spaces and their heritage. Participant observation also identified the interrelationship between the community and urban public spaces, and identified problems and trends associated with their management, purposes, and preservation.

Focus groups established relationships among participants and analyzed the different points of view associated with the transformations of urban public spaces, their use and consumption values, and the main problems they face. They also analyzed the contemporary challenges in each context, with special emphasis on the area declared a National Monument within the Historic Urban Center of the city of Matanzas. Topics related to cultural identity, urban sustainability, and the government’s commitment to proper management were also discussed by the research team. Institutions that have carried out sustained work to safeguard these public spaces and the values associated with them were highlighted.

Data Analysis Methods

The collected data were analyzed using content analysis and a triangulation of methods, techniques, sources, and data. This design allowed for the identification of emerging categories and the establishment of relationships between concepts and definitions. The results were triangulated with the various findings from the documentary review, observation, interviews, and focus groups to ensure greater validity and consistency in the discussions and conclusions. This methodology combined qualitative techniques with a case study approach and documentary review to explore in-depth and contextualized terms the relationship between the resident community and the public spaces of the Historic Urban Center of Matanzas. Furthermore, it was possible to identify the complexity of local dynamics in the sustainable management of its heritage.

RESULTS

This study identified that the community residing in urban public spaces plays an essential role in the construction and preservation of their heritage. It should be noted that for this study, the inclusion of natural heritage was adopted in the classification of cultural heritage; in turn, this cultural heritage is composed of tangible or material elements and intangible or immaterial ones. The instruments used for data collection allowed us to affirm that public spaces not only function as areas of transit, leisure, or recreation (Bleibleh & Awad, 2024) but that cultural interaction, identity promotion, and the consolidation of collective memory also take place there.

The social dynamics that develop in these spaces are closely related to the daily practices of their inhabitants and are an expression of living heritage. Molari et al. (2024) state that, in this case, intangible elements converge with tangible elements, such as buildings, parks, plazas, promenades, avenues, small squares, pedestrian walkways, recreational areas, sports, and cultural complexes, among others.

Figure 1 shows three fundamental areas; the red one is the Urban Historic Center of the city of Matanzas, the yellow one is the Priority Conservation Zone, and the green one is the one declared a National Monument. The present research focused on the latter.

|

Figure 1. Study area of urban public spaces |

|

|

Source: Cabrera Valdés (Ed.) (2024)

It was observed how trends in the management of urban public spaces show greater community inclusion in planning and conservation processes. Previously, we addressed the challenges faced by many heritage cities due to their failure to take into account the perceptions, criteria, and assessments of the resident community. Some of these decisions are made top-down, without considering the needs and expectations of the host community, which is also the driving force behind the cultural values manifested in these urban public spaces.

This study highlighted the importance of active community participation, not only as creators of public spaces but also as their managers (Mishra et al., 2020). This strengthens the sense of belonging and contributes to the sustainability of the rehabilitation, restoration, and conservation actions carried out in these spaces. The fact that communities take ownership of their public spaces generates care for them, a demand for the creation of cultural activities (Farstad & Aarsand, 2021), the care of green areas, their cleanliness, and an understanding of heritage as a common good, which requires commitment from all parties.

The focus group discussions also identified the function of public spaces as settings for the expression of cultural diversity and the most indigenous traditions of their inhabitants. It is possible to appreciate how different identities, traditions and worldviews, intangible heritage, trades, traditions, collective social practices, and artistic expressions converge. These, together, integrate the urban fabric and give it a unique and singular character. They constitute a strength for local communities, becoming their greatest attractions for national and foreign visitors. In this case, alliances and collaborations between the community, institutions, and local governments are necessary. One of the problems associated with the management of public spaces in heritage cities is gentrification as a phenomenon and the privatization of specific spaces. Authors such as Hamza et al. (2024) agree that this generates exclusion, limits accessibility, and influences the loss of identity for some social groups. This is what the authors of this article refer to when they state that there are currently public spaces that reserve the admission of specific individuals based on criteria established by the institutions themselves.

Regarding practical experiences, through interviews and analysis of sources on the topic, it was possible to verify that there are community-generated initiatives that have had a significant impact on the rehabilitation of public spaces. Therefore, this work is not only recognized by the technicians for the intervention of specific spaces but also by the community itself (Dezio & Paris, 2023).

Collaborative projects in green areas and riverbanks, the creation of collective murals, and local fairs that demonstrate citizen action from non-formal educational contexts stand out. All of this demonstrates how it is possible to positively transform the environment in line with public policies (Guillard & McGillivray, 2022) and heritage preservation objectives. It is also evident how, in local development projects, communities and institutions collaborate to diversify the cultural (Tuhkanen et al., 2022), tourism, and heritage offerings in these settings. These findings demonstrate that heritage is not static but rather evolves according to the needs of communities (Gómez Cano et al., 2024).

The interrelationship between the community and urban public spaces is a key element for the preservation and revitalization of heritage. This active participation requires institutional commitment and support that recognizes the serious, committed, and conscious work of the community. This also fosters cultural diversity and the promotion of sustainable practices as fundamental pillars in the management of public spaces (Tarlao et al., 2024).

The importance of taking into account current challenges, including gentrification, social fragmentation, and the need for a participatory and inclusive approach, always prioritizing collective well-being, is highlighted. It also highlights the prevailing actions to safeguard heritage as a living and constantly changing legacy (Wang et al., 2024). Table 1 shows the population of the municipality of Matanzas. Of this population, only approximately 11.3% live in the area declared a National Monument. This demonstrates that this small percentage has direct access to urban public spaces and is, therefore, their greatest beneficiary. The remainder uses them as recreational spaces, so proper management of these spaces generates greater commitment to them and access.

|

Table 1. Population of Matanzas municipality |

||||

|

Number |

Demarcation |

Extension (Ha) |

Population |

% of the City's Population |

|

1 |

Versalles |

928.52 |

18972 |

13 |

|

2 |

Matanzas Este |

149.54 |

19963 |

13.7 |

|

3 |

Matanzas Oeste |

312.6 |

26315 |

18.1 |

|

4 |

Naranjal |

704.01 |

12712 |

8.7 |

|

5 |

Pueblo Nuevo |

937.5 |

36031 |

24.8 |

|

6 |

Playa |

324.9 |

5774 |

4 |

|

7 |

Peñas Altas |

316.18 |

16866 |

11.6 |

|

8 |

Canímar |

957.58 |

8953 |

6.1 |

|

|

Total |

4 630.83 |

145586 |

100 |

Fuente: Cabrera Valdés (Ed.) (2024)

DISCUSIÓN

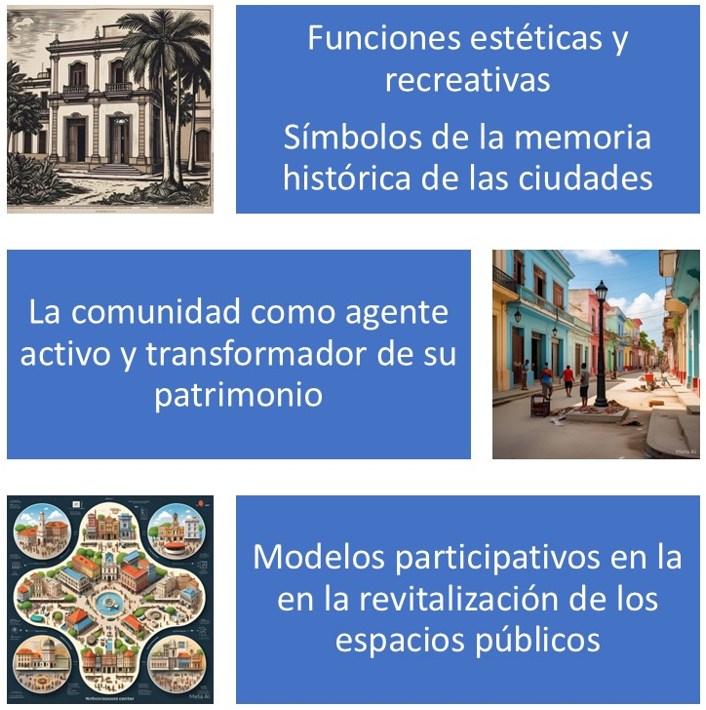

It is necessary to address once again how, in the literature reviewed and in all the instruments used for data collection, the importance of the relationship between the community and urban public spaces was affirmed. This constitutes the most excellent preserver of its heritage and, furthermore, confers use value on it and reconstructs it daily (figure 2). This topic, in the Latin American context, is highly relevant in the sense that public spaces in these countries have been sites of struggle, resistance, and the construction of collective identities.

|

Figure 2. Premises in the relationship between community and public spaces |

|

|

Source: own elaboration

Note: the figure appears in its original language

Furthermore, many are in optimal condition to be displayed in their original form. In contrast, in other nations, significant changes are observed in the structure of urban public spaces associated with the drive to modernize cities and the implementation of new styles that break with their original physiognomy (O'Neill et al., 2023).

These public spaces not only have aesthetic and recreational functions but also constitute symbols of the historical memory of cities. One of the main trends is the recognition of the community as an active agent and transformer of its heritage. This allows us to contrast how traditional practices, intangible heritage, and living elements are distinguished in urban planning. Figure 3 shows the essence presented so far about urban management in heritage cities and the role of the community.

|

Figure 3. Conclusions reached from the analysis of documentary sources |

|

|

Source: own elaboration

Note: the figure appears in its original language.

Participatory models demonstrate positive experiences such as the recovery of plazas, parks, corridors, and pedestrian walkways, as well as the revitalization of unused public spaces and social progress, coupled with community experiences and initiatives defending their heritage against gentrification.

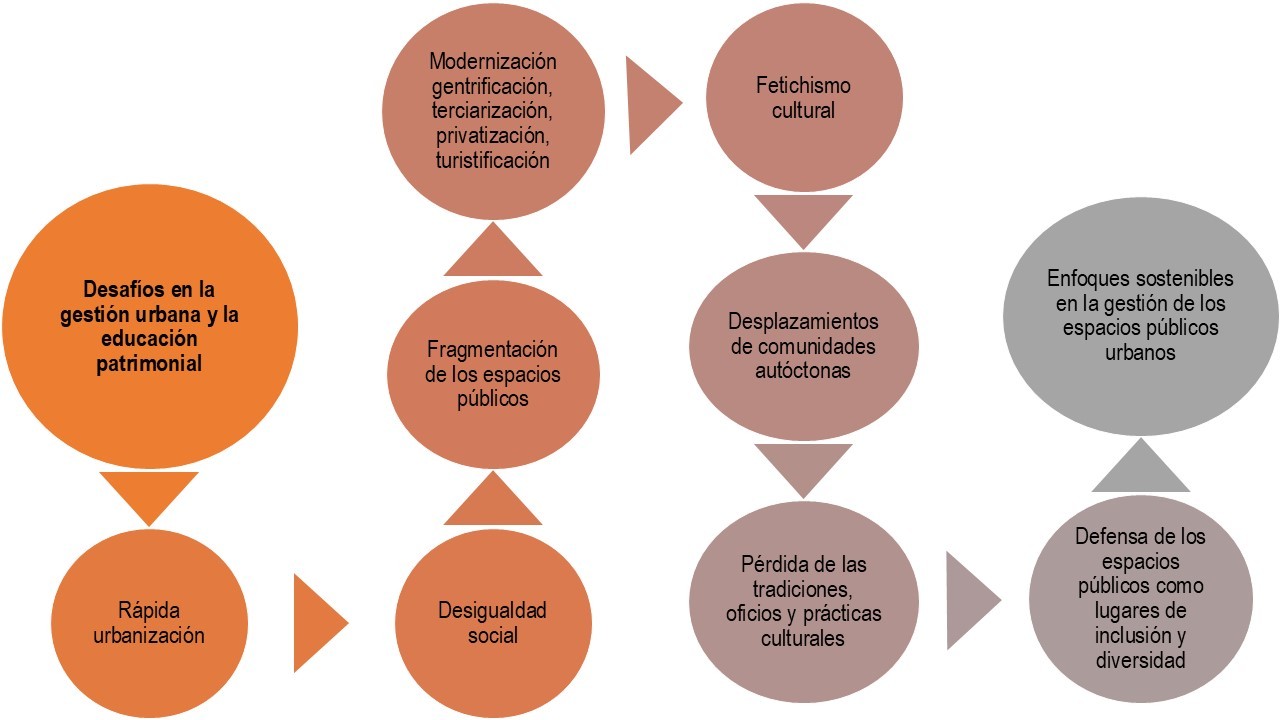

Correspondingly, challenges and issues to be resolved in Latin American governance are evident, associated with rapid urbanization, social inequality, the fragmentation of public spaces, and their modernization and privatization. In many cases, local governments covertly displace communities by failing to design public policies that protect these indigenous communities, giving rise to the interference of other sectors that do not carry these traditions or identify with the local heritage.

This also leads to another problem affecting historic and heritage cities, such as tertiarization. This consists of the fact that, as local communities are displaced from their homes near public spaces, these spaces become venues for commerce, sales, and businesses, which are closed and non-functional during certain times of the year.

Many social movements are taking place to demand the right to the city and defend public spaces as places of inclusion and diversity. All of this highlights the importance of urban life, social commitment, and the existence of public (and also private) models and policies that benefit collective well-being above economic profit.

Latin American cultural diversity distinguishes public spaces, unlike in other regions. These spaces are characterized by being meeting places for multiple identities and traditions that converge and are shaped without displacing or emphasizing one over the other.

The importance of sustainable approaches in the management of urban public spaces is also highlighted, not only from an environmental perspective but also from a social and artistic perspective. In Latin America, resources are limited, and the challenges are increasingly greater. For this reason, community initiatives are proving to be an alternative for the rehabilitation of degraded areas and damaged public spaces.

Experiences in this regard have already been mentioned, such as the creation of gardens, green areas, trees, and the restoration of rivers and other ecosystems that are part of the urban fabric and linked to public spaces (Martí et al., 2020). These initiatives are also associated with the use of renewable energy, the use of non-motorized transportation equipment, creative economies, the use of recycled raw materials, and other sustainable elements. These practices contribute to improving the quality of life of residents and strengthening the connection between the community and its environment. An analysis of the different research methods applied, and the results of the sources consulted allowed us to develop the following graph (figure 4), which summarizes the challenges that heritage cities face in implementing proper urban management and community participation.

|

Figure 4. Challenges in urban management and heritage education |

|

|

Source: own elaboration

Note: the figure appears in its original language.

The study revealed the importance of the relationship between the community and urban public spaces. This is a key issue for the preservation of local heritage. The management of the Urban Historic Center of Matanzas, Cuba, was used as a case study. Through the use of data collection instruments, the study verified its correspondence with the analyzed theoretical sources, reflecting other international experiences.

It also reveals the need to address contemporary challenges from a comprehensive perspective, combining citizen participation, recognition of cultural diversity, and environmental sustainability. This inclusive and collaborative approach will enable these spaces to serve as venues for the convergence of identities and the reconfiguration of heritage for present and future generations.

CONCLUSIONS

The study demonstrates the important role of the community in safeguarding its traditions, rescuing its heritage, and managing urban public spaces. Their active participation contributes to diversifying the cultural offering, creating an adequate infrastructure for tourism, and contributing to environmental sustainability. All of this is achieved when local authorities and goernments are able to take into account the empirical wisdom of community members and specialists from the institutions surrounding them.

Suppose the community identifies with and feels part of the processes, as well as beneficiaries of the income and services generated by tourism. In that case, they can contribute more actively to the sustainability of public spaces and the socialization of their cultural heritage in the broadest sense. These spaces allow, in addition to recreation, the expression of cultural diversity and the formation of social representations, traditions, and expressions of popular culture.

Challenges associated with gentrification, privatization, and outsourcing in public spaces were identified, with a special emphasis on Latin American heritage cities. These impact historic cities and their management in every sense (urban, heritage, environmental, artistic). Despite this, the literature reviewed highlights positive experiences in the rehabilitation of public spaces and the diversification of cultural offerings, the generation of actions for environmental sustainability and ecosystem protection. It is necessary to integrate communities, institutions, and local governments, in addition to public and private policies that contribute to promoting social equity, prioritizing collective well-being, and maintaining these spaces as spaces for meeting, remembering, and preserving identity.

REFERENCES

Bernabeu Bautista, Á., Serrano Estrada, L., & Martí, P. (2023). The role of successful public spaces in historic centres. Insights from social media data. Cities, 137, 104337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104337

Blečić, I., Cois, E., Muroni, E., & Saiu, V. (2024). Spaces seeking activities—Activities seeking spaces: Evaluation and policy design of neighbourhood-wide urban community spaces. City, Culture and Society, 39, 100606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2024.100606

Bleibleh, S., & Awad, S. (2024). Everyday lived experience and ‘carescape’ of women street vendors: Spatial Justice in Al-Hisba Marketplace, Ramallah/Al-Bireh, Palestine. Geoforum, 153, 104014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2024.104014

Cabrera Valdés, M. A. (Ed.) (2024). Plan de Desarrollo Integral 2023. Zona priorizada para la conservación de la ciudad de Matanzas. Oficina del Conservador de la Ciudad de Matanzas. Cuba.

Ciacci, C., Banti, N., Naso, V. D., & Bazzocchi, F. (2023). Green strategies for improving urban microclimate and air quality: A case study of an Italian industrial district and facility. Building and Environment, 244, 110762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110762

Dezio, C., & Paris, M. (2023). Three case studies of landscape design project of Italian marginal areas. An anti-fragile opportunity for an integrated food governance in a post Covid perspective. Cities, 135, 104244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104244

Duignan, M., Carlini, J., & McGillivray, D. (2023). Parasitic events and host destination resource dependence: Evidence from the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 30, 100796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2023.100796

Farstad, I. E., & Aarsand, P. (2021). Children on the move: Guided participation in travel activities. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 31, 100546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2021.100546

Fior, M., Galuzzi, P., & Vitillo, P. (2022). New Milan metro-line M4. From infrastructural project to design scenario enabling urban resilience. Transportation Research Procedia, 60, 306-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2021.12.040

García Mayor, C., Bernabeu Bautista, Á., & Martí, P. (2025). The contribution of geolocated data to the diagnosis of urban green infrastructure. Tenerife insularity as a benchmark. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 107, 128756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2025.128756

Gargiulo, C., & Sgambati, S. (2022). Active mobility in historical centres: Towards an accessible and competitive city. Transportation Research Procedia, 60, 552-559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2021.12.071

Gómez Cano, C. A., Sánchez Castillo, V., & Pérez Gamboa, A. J. (2024). Formación integral y configuración de proyectos de vida: consideraciones para la adecuada atención psicopedagógica de estudiantes en la educación superior. Miradas, 19(2), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.22517/25393812.25683

Guillard, S., & McGillivray, D. (2022). Eventful policies, public spaces and neoliberal citizenship: Lessons from Glasgow. Cities, 130, 103921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103921

Hamza, M., Edwards, R. C., Beaumont, J. D., Pretto, L. D., & Torn, A. (2024). Access to natural green spaces and their associations with psychological wellbeing for South Asian people in the UK: A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 359, 117265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117265

Herrmann Lunecke, M. G., Figueroa Martínez, C., & Espinoza, B. O. (2024). Older persons’ emotional responses to the built environment: An analysis of walking experiences in central neighbourhoods of Santiago de Chile. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 28, 101279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2024.101279

Jiménez Pérez, G. A., Domínguez Albear, Y., & Santos Fernández, J. P. (2025). La Educación Patrimonial en Espacios Públicos. Journal of Scientific Metrics and Evaluation, 3(1), 29-50. https://doi.org/10.69821/JoSME.v3i1.19

Legg, S. (2025). Contesting monuments: Heritage and historical geographies of inequality, an introduction. Journal of Historical Geography, 87, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2024.09.005

Martí, P., García Mayor, C., Nolasco Cirugeda, A., & Serrano Estrada, L. (2020). Green infrastructure planning: Unveiling meaningful spaces through Foursquare users’ preferences. Land Use Policy, 97, 104641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104641

Mishra, H. S., Bell, S., Vassiljev, P., Kuhlmann, F., Niin, G., & Grellier, J. (2020). The development of a tool for assessing the environmental qualities of urban blue spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 49, 126575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126575

Molari, M., Dominici, L., Manso, M., Silva, C. M., & Comino, E. (2024). A socio-ecological approach to investigate the perception of green walls in cities: A comparative analysis of case studies in Turin and Lisbon. Nature-Based Solutions, 6, 100175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbsj.2024.100175

O’Neill, E., Cole, H. V., García Lamarca, M., Anguelovski, I., Gullón, P., & Triguero Mas, M. (2023). The right to the unhealthy deprived city: An exploration into the impacts of state-led redevelopment projects on the determinants of mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 318, 115634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115634

Pereira, A., & Rebelo, E. M. (2024). Women in public spaces: Perceptions and initiatives to promote gender equality. Cities, 154, 105346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.105346

Peterson, M. (2024). Designing a feminist city: Public libraries as a women’s space. Geoforum, 150, 103971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2024.103971

Tarlao, C., Leclerc, F., Brochu, J., & Guastavino, C. (2024). Current approaches to planning (with) sound. Science of The Total Environment, 931, 172826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172826

Tuhkanen, H., Cinderby, S., Bruin, A. de, Wikman, A., Adelina, C., Archer, D., & Muhoza, C. (2022). Health and wellbeing in cities—Cultural contributions from urban form in the Global South context. Wellbeing, Space and Society, 3, 100071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wss.2021.100071

Vazquez, S. A., Madureira, A. M., Ostermann, F. O., & Pfeffer, K. (2024). Challenges and opportunities of public space management in Mexico. Cities, 146, 104743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104743

Wang, L., Hou, C., Zhang, Y., & He, J. (2024). Measuring solar radiation and spatio-temporal distribution in different street network direction through solar trajectories and street view images. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 132, 104058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2024.104058

Wang, S., & Vu, L. H. (2023). The integration of digital twin and serious game framework for new normal virtual urban exploration and social interaction. Journal of Urban Management, 12(2), 168-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2023.03.001

Yang, C., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Public emotions and visual perception of the East Coast Park in Singapore: A deep learning method using social media data. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 94, 128285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128285

Zarie, E., Sepehri, B., Adibhesami, M. A., Pourjafar, M. R., & Karimi, H. (2024). A strategy for giving urban public green spaces a third dimension: A case study of Qasrodasht, Shiraz. Nature-Based Solutions, 5, 100102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbsj.2023.100102

FINANCING

None.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez, José Manuel Hernández de la Cruz and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.

Data curation: José Manuel Hernández de la Cruz and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.

Formal analysis: Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez, José Manuel Hernández de la Cruz and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.

Research: Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez, José Manuel Hernández de la Cruz and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.

Methodology: José Manuel Hernández de la Cruz and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.

Project administration: Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez.

Software: Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez and José Manuel Hernández de la Cruz.

Supervision: José Manuel Hernández de la Cruz and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.

Validation: Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.

Visualization: Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.

Writing – original draft: Guillermo Alfredo Jiménez Pérez.

Writing – proofreading and editing: José Manuel Hernández de la Cruz and Ana Gloria Peñate Villasante.