doi: 10.58763/rc2024339

Scientific and Technological Research

Military education. A look from security and defense

Educación militar. Una mirada desde la seguridad y defensa

Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo1 ![]() *,

Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz1

*,

Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz1 ![]() *

*

ABSTRACT

The education, in the military environment, has different looks for its analysis. Among the possible focuses, they are the aspects of security and defense, being these the spine of the military forces. Starting from an analysis regarding the security and defense in the field of the military education, and applied to the Colombian national context, the present study had as objective to meditate on the formation of the military one, taking as reference scenario the military teaching in the aerospace formation, in a specific way: the Military School of Aviation (EMAVI) and the School of Posgraduate of the Colombian Aerospace Force (EPFAC). In that way, together to the analysis of bibliographical sources on the thematic one, the article presents general considerations on the topic of the security and the defense, followed by a look to the national internal conflict and the experience in the aviator’s formation at the present time.

Keywords: armed conflict, military education, the military aviator’s formation, security and national defense.

JEL Classification: I20, I21, I29

RESUMEN

La educación, en el ámbito militar, tiene diferentes miradas para su análisis. Entre los posibles enfoques, se encuentran los aspectos de seguridad y defensa, que son la columna vertebral de las fuerzas militares. A partir de un análisis a la seguridad y defensa en el campo de la educación militar, y aplicado al contexto nacional colombiano, el presente estudio tuvo como objetivo reflexionar sobre la formación del militar, tomando como escenario de referencia la enseñanza militar en la formación aeroespacial; de forma específica: la Escuela Militar de Aviación (EMAVI) y la Escuela de Posgrados de la Fuerza Aeroespacial Colombiana (EPFAC). De ese modo, unido al análisis de fuentes bibliográficas sobre la temática, el artículo presenta consideraciones generales sobre el tema de la seguridad y la defensa, seguidas de una mirada al conflicto interno nacional y la experiencia en la formación del aviador en la actualidad.

Palabras clave: conflicto armado, educación militar, formación del aviador militar, seguridad y defensa nacional.

Clasificación JEL: I20, I21, I29

Received: 02-03-2024 Revised: 25-05-2024 Accepted: 15-06-2024 Published: 01-07-2024

Editor:

Carlos Alberto Gómez Cano ![]()

1Escuela de Posgrados de la Fuerza Aeroespacial Colombiana. Bogotá, Colombia.

Cite as: Gómez, R. y Rojas, Z. (2024). Educación militar. Una mirada desde la seguridad y defensa. Región Científica, 3(2), 2024339. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2024339

INTRODUCTION

The security and defense of a country are fundamental pillars for its stability and development. In this regard, military education is of great importance, not only in the training of soldiers and officers, but also in strengthening a nation's strategic and tactical capabilities. This article allows us to reflect on the importance of military education in a country's security and defense, highlighting its impact on officer training and its contribution to national peace and security.

War and its consequences are a phenomenon derived from political activity; its nature does not change, but how battles are fought does. In retrospect, it is possible to affirm that war persists as a reality of human society, although battles tend to change over time, driven by strategic and tactical changes related to the transformation of knowledge.

It is important not to overlook the problem of the political demands present in this scenario (Niño and Palma, 2023; Vélez-Torres and Méndez, 2022). War, as a continuation of politics, is part of the dynamics of international relations, where concerns such as security and defense cannot rule out the possibility of using military power (Amoroso et al., 2023).

Colombia has experienced decades of armed conflict that have left deep scars on its society (Bernal et al., 2024; Camargo et al., 2020), and the peace process and the post-conflict transition present a unique opportunity to rebuild and strengthen the country (Barrera et al., 2022; Cárdenas, 2023; Naranjo-Valencia et al., 2022). In this context, military education plays a crucial role in consolidating peace, promoting security, and contributing to national development (Fernandez-Osorio et al., 2023; Pineda & Celis, 2022).

In an effort to reflect on these aspects, this study was divided into three parts: the first addresses introductory considerations on the topic of security and defense; the second addresses the history and training of Colombian Aerospace Force officers; and the third, more specifically, examines the officers' achievements, seeking to demonstrate the quality of their training.

METHODOLOGY

Approach, analysis of sources and context

From a methodological perspective, this reflection article is based on research that followed a qualitative approach, seeking to delve deeper into the understanding of military education through documentary review and self-referential and ethnographic analysis of experiences and success stories. Data were also collected from primary and secondary sources related to the importance of military education, facilitating the triangulation and representation of the findings and assessments (Natow, 2020).

From a self-referential perspective, this reflection is based on three fundamental processes: analysis of the field diary, critical reflection, and assessment of one's own experiences. To achieve these results, field diaries were kept, which provided details about the authors' personal experiences; participants shared and reflected on these experiences and how gender perspectives and life development influenced them; personal narratives were also contrasted to integrate the authors' personal experiences, the academic analysis offered by the literature, and the success stories examined.

Thus, triangulation was intended to transform these personal data, reflections, and narratives into a valuable data set that facilitated ongoing comparison, as well as the identification of convergences, divergences, and common patterns (Lemon & Hayes, 2020). This triangulation approach strengthened the credibility of the findings and the scientific-academic value of the assessments offered in this reflection text without abandoning the ethnographic and critical approach (Mohr et al., 2021; Sørensen & Weisdorf, 2021).

This paper presents, in general terms, how international authors address the importance of national security and defense, as well as their perspective on the conflict in Colombia. In addition, the professionalization of military education in the country is valued, starting with the training of military aviators at the Military Aviation School (EMAVI) and the Colombian Aerospace Force Postgraduate School (EPFAC), in addition to the importance of Colombian officers.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Security and defense: national interests

The security of a nation has its origins thousands of years ago when the first men and women who populated the planet had to face hostile natural environments in order to safeguard their lives and those of their families, resources, and means of survival. Then, with the increase in population, struggles for territories, natural resources, and better living conditions began. At that moment in history, one could refer to war. It has changed in its form, means, strategies, and other constituent factors; it is considered valid to the extent that it allows states to regain stability.

Over time, security and defense have transformed to the point of becoming what they are today, with their triggering factors, characteristics, and consequences. In the specific case of Colombia, the Political Constitution (Article 217) clarifies the meaning of the military forces, their structure (Army, Navy, and Air Force), and their objective, based on the independence, defense, and sovereignty of the national territory.

In this regard, and to fulfill this mission, the Colombian Aerospace Force aims to conquer and dominate the air, space, and cyberspace, thus contributing to the goals of the State. However, this has not been an easy task; Colombia has had a unique reality, responding to the country's unique needs. The internal conflict, which has lasted for decades, is caused by the violence of those struggles that arose from the bipartisan struggle for power. The emergence of these conflicts dates back to the beginning of the 20th century and intensified in the late 1940s, a historical moment in which liberals and conservatives, seeking to gain political power, chose to implement practices that included eliminating their adversaries in terms of their ideas and economic interests.

From 1960 onwards, the conflict was formalized when political, social, and peasant struggles gave rise to illegal armed groups, including the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN), formed in 1964. Initially, their manifestos suggested that they were committed to vindicating the rights of the peasant population and the less fortunate, using weapons as a means of pressure. Three years later, the Popular Liberation Army (EPL) emerged, and at the beginning of the following decade, following distrust in the 1970 electoral process, the April 19 Movement, known as M-19, emerged (Arias, 2020; Acero & Machuca, 2021).

With these new guerrilla groups, a period of violence ensued that turned the country into one of the most conflict-ridden countries in the world. Thus, violence would become a problem that would undermine Colombian society in its social, economic, political, and environmental dimensions. This, among other consequences, led to insecurity in the territories, as the numerous armed groups and their respective fronts began to exceed the capacities of the legitimate military forces of the State to maintain public order, especially in areas far from population centers (Prem et al., 2020; Georgi, 2022; Holmes et al., 2023).

This entire war landscape led the Colombian military forces to focus on these scenarios. This scenario began to change after the signing of the Peace Agreement, recognizing the main challenges for the military forces as those associated with security in the territories abandoned by the FARC. It is also important to note that other illegal groups may occupy them, and in the meantime, public order may not be consolidated, and criminal practices may continue or intensify (Culma & Tatiana, 2021).

None of this would be possible without highly qualified personnel whose training is not limited to mastering the use of weapons but rather to other areas of military training with a high axiological content. This is established in basic documents of the air forces, such as COGFM Provision 001 of January 2021 and Ministerial Resolution 0192 of February of that same year. Highly qualified human resources are required, committed to the institution and, even more so, to the development of air operations demanded by the nation (Fernández-Osorio et al., 2023).

Military education benefits the armed forces and national and international security (Figueroa, 2023). Well-trained officers can contribute to internal stability through public order maintenance and emergency management operations. Furthermore, military education fosters international cooperation through exchange programs and joint training with other countries, promoting global peace and security.

The core values instilled are honor, duty, loyalty, and discipline. These are essential for success on the battlefield and for the cohesion and morale of the army. The discipline and rigor of military training ensure that soldiers and officers are prepared to face any challenge with integrity and professionalism.

Education and training in the aerospace force: A historical approach to the professionalization of military aviators in Colombia

Today, education is recognized as one of the fundamental pillars of vocational training. This was not always the case; the earliest references to ancient Greece show that personal skill and valor were crucial, rather than military training.

In Colombia, an academy for the training of officers was established at the beginning of the 20th century, thus giving rise to formal military training. The armies fighting during the independence and civil wars of the 19th century did not do so based on training in military academies or schools. The difficult economic situation in the Republic's early years made this type of training impossible. Despite this, Generals Pedro Alcántara Herrán (1841-1845) and Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera (1845-1849) stood out during this period, advocating for the professionalization of Colombian troops.

The first subjects to be taught were strategy and tactics, construction, and civil engineering since Colombia was a country in formation, and the officer was identified as suitable for this challenge. However, attempts to open a Military College were short-lived for political reasons. Subsequent attempts failed due to civil wars and the political weakness of a fragmented state incapable of consolidating a central government.

It wasn't until well into the 20th century that this idea materialized again during the government of Rafael Reyes (1904) under the premise of professionalizing military education to achieve greater internal political stability. The following year, Rafael Uribe was appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the governments of Chile, Argentina, and Brazil. After studying the Chilean army, he recommended hiring a mission from that country to contribute to professionalizing the military in Colombia.

However, the government's will was not without resistance, especially from those affected by the reform: officers belonging to the regional elites who saw the reform as a risk to their stability. This tension would be the cause of the advances and setbacks in the early years. This scenario existed in 1919 when aviation was created as the fifth branch of the Army. As expected, the large percentage of students were officers from different branches, especially cavalry. During the first decades, the School was influenced by the doctrine and programs of the Military Cadet School.

The first directors were completely unfamiliar with aviation and were assigned only "on secondment" to the Aviation School. Decree 2247 of December 23, 1920, which contained regulations on the organization and operation of the School with regard to academic preparation, established as requirements for obtaining a military pilot license knowledge of the functions and mechanics of aircraft, in addition to mastering chart reading and aerial navigation.

The government contracted a French mission under Colonel René Guichard to train and maintain the nascent aviation industry. After an inspection conducted in 1922 by the Minister of War, it was determined that the training was exclusively practical since the theoretical aspect, which should have been carried out by Colonel Guichard, was not provided due to language difficulties.

Thus passed the first decades, marked by periods in which the School closed its operations and European missions (French and Swiss) were contracted. In the 1940s and 1950s, training became specialized, and subjects such as aerodynamics, navigation, meteorology, and the use of equipment such as radios were introduced. As aircraft became more complex, education became more rigorous and specialized. In addition, the American Mission, which arrived in Colombia at that time, transmitted all the experience that the country had acquired.

Thus, beginning in 1960, the Air Force believed its officers needed to be better prepared to operate in an increasingly complex society and environment. The Ministry of National Education approved the proposed university programs; cadets completed their first two years of engineering or economics at the School, and later in their careers, students transferred to universities where they could complete their studies.

Experiences at two prominent institutions: the Military Aviation School (EMAVI) and the Colombian Aerospace Force Postgraduate School (EPFAC)

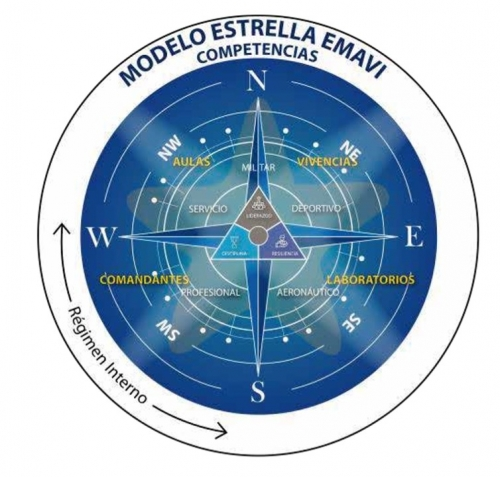

The Marco Fidel Suarez Military Aviation School is a high-quality, accredited higher education institution that trains officers to carry out operations in the field of aeronautics for the purposes of national defense and security. To this end, it has four professional training programs: Aeronautical Administration, Aeronautical Military Sciences, Computer Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering, based on the “Star” model, which is based on five components: military, sports, aeronautical leader, professional and service, as shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1. EMAVI Star Model |

|

|

Source: EMAVI

Note: the figure appears in its original language

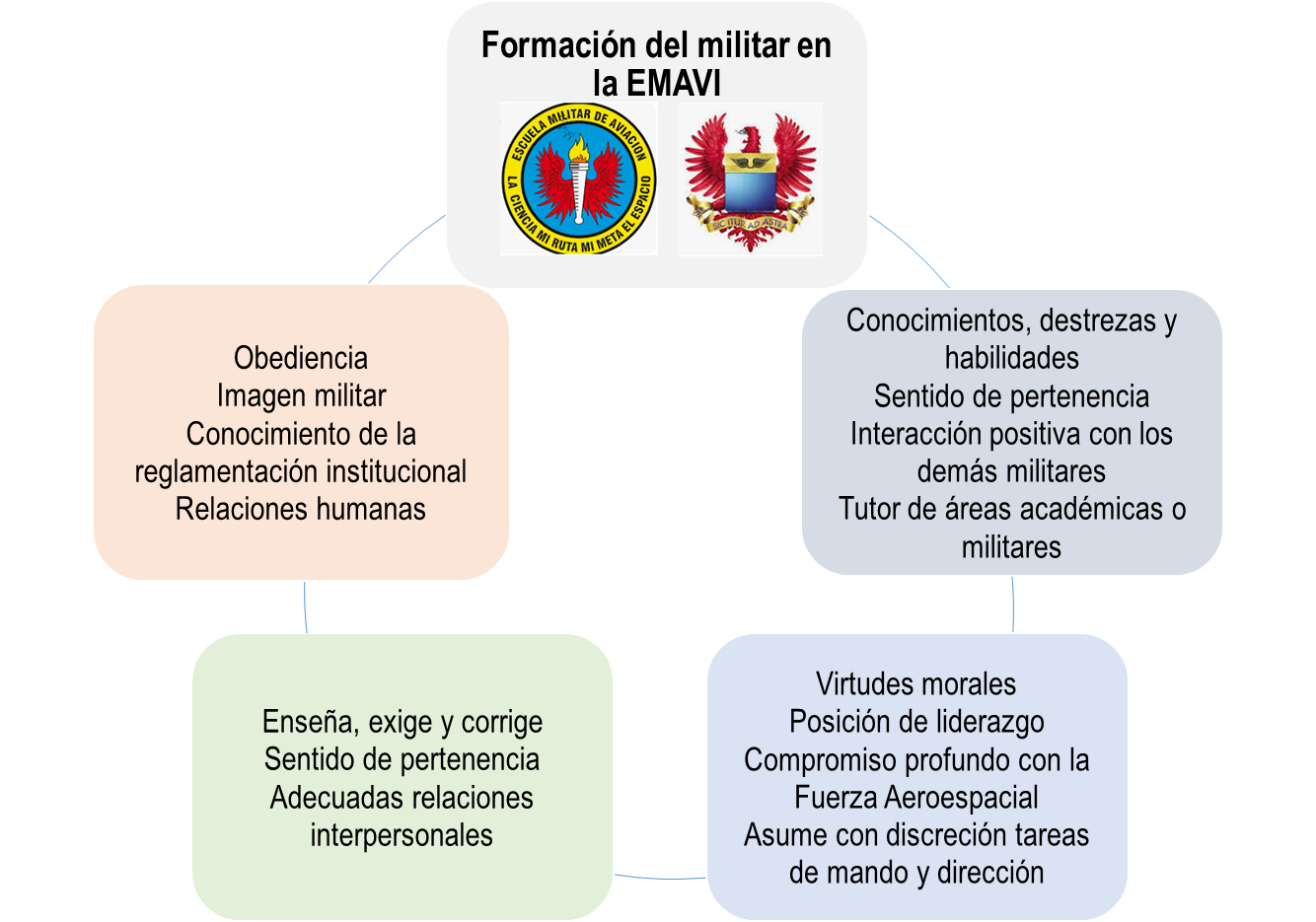

In their training, future soldiers, once they graduate from EMAVI, go through a four-stage process: the first three as a cadet and then as a second lieutenant. During these stages, they are taught content specific to their training area, in addition to providing them with characteristic elements to cement their role as soldiers. Figure 2 highlights the specific characteristics they are expected to acquire each year.

|

Figure 2. Military training at EMAVI |

|

|

Source: Own elaboration

Note: the figure appears in its original language

Likewise, the Colombian Aerospace Force Postgraduate School contributes to military training. These include promotion courses, including the first Tactical Leadership Course of the Administrative Corps, lasting eight weeks, for officers promoted from lieutenant to captain. There is also the Tactical Leadership Course, lasting 18 weeks, for officers promoted from captain to major. The School also offers four advanced master's programs recognized by the Ministry of Education: the Master's in Military Aeronautical Sciences (MACMA), with SNIES 102792; the Master's in Operational Security (MAESO), with SNIES 102978; the Master's in Aeronautical Logistics (MAELA), with SNIES 102645; and the Master's in Comprehensive Security (MADGSI), with SNIES 105360. Each of these postgraduate programs addresses the specific needs of the FAC. It should be noted that the first program is offered exclusively to military personnel in the flight corps, while the other three are open to civilian personnel. To date, there have been a total of 276 graduates, distributed by program, as shown in table 1:

|

Table 1. Graduate of EPFAC |

|

|

Master's program |

Total graduates |

|

Macma |

132 |

|

Maela |

49 |

|

Maeso |

52 |

|

Magdsi |

43 |

|

Total |

276 (until 2024) |

Source: prepared by the authors based on SEGRE statistics

From weapons to classrooms

Applying acquired knowledge and skills in specific situations becomes even more important with the major transformations in today's world, which create a point of convergence and balance between the skills provided by competency-based education and the instability generated by these changes in today's world (Crecente et al., 2021). Military education is essential for developing skilled and competent leaders who can make critical decisions in high-pressure situations. Military training programs, such as war academies and colleges, provide officers with the necessary skills in strategy, tactics, leadership, and resource management. These leaders are responsible for leading combat troops and planning and executing complex operations that require a deep understanding of geopolitics and battlefield dynamics.

One of the greatest post-conflict challenges is the reintegration of former combatants into civilian life (Boulanger Martel, 2022; Pérez et al., 2023). Military education can offer training and technical development programs that facilitate this process. By providing transferable skills and employment opportunities, military education helps prevent a recurrence of violence and contributes to building lasting peace. Furthermore, targeted demobilization and reintegration programs that include educational components can help ex-combatants develop a sense of purpose and belonging in civil society (Elston, 2020; Gutiérrez & Murphy, 2023).

The Colombian armed forces must transform and professionalize in the post-conflict context to fulfill their new roles and responsibilities. Advanced military education, which includes training in human rights, international humanitarian law, and conflict management, is vital to ensure that the military acts with integrity and respect for the civilian population. The professionalization of the armed forces not only improves their operational effectiveness but also strengthens citizens' trust in state security institutions.

In a world of rapidly advancing technology, military education is essential to ensuring that the armed forces are at the forefront of the latest innovations. Military higher education institutions play a vital role in researching and developing new tactics and technologies, ensuring the country is prepared to face modern threats (Carrillo, 2020).

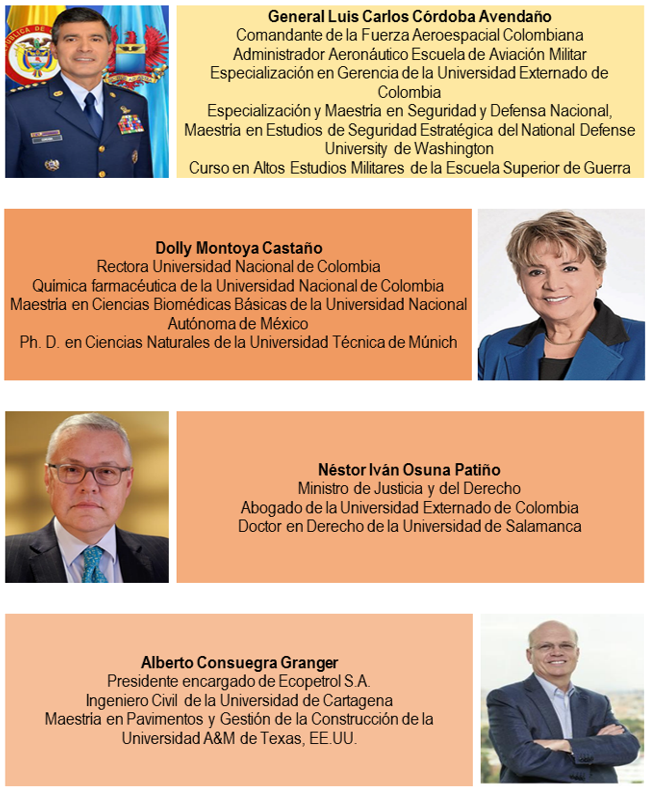

To this end, they rely on highly qualified and skilled personnel (Li et al., 2020; Jiménez, 2020; Jenne, 2020). Currently, the Colombian Aerospace Force is commanded by General Luis Carlos Córdoba Avendaño, who, in addition to his experience, has an academic background that is often unknown to the general public, as officers are typically viewed as simple, academically speaking.

However, a review of the academic profiles of important figures in the country reveals that the Commander of the Colombian Aerospace Force (COFAC) has an advanced academic profile.

|

Figure 3. General Luis Carlos Córdoba Avedaño's status compared to other Colombian figures |

|

|

Source: own elaboration

Note: the figure appears in its original language

Achievements of officers that transcend the institution to the nation

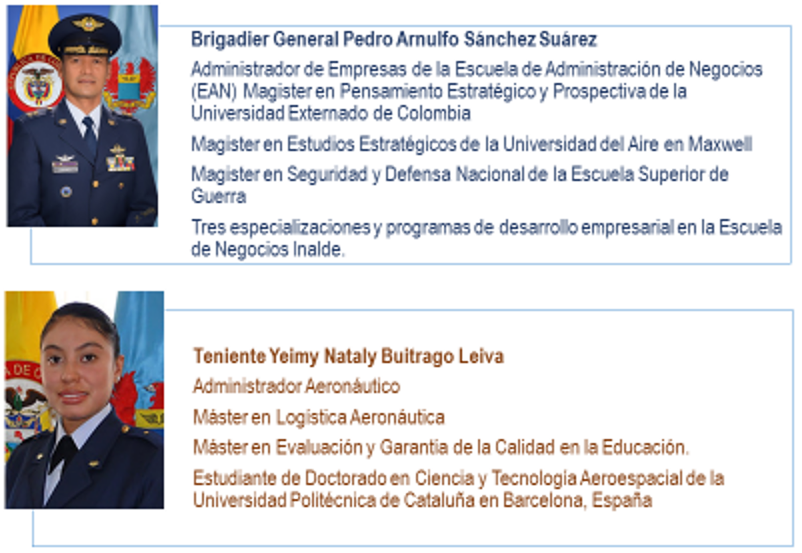

The academic training of Colombian Aerospace Force officers is a never-ending task. In addition to pursuing postgraduate master's and doctoral degrees, they regularly take refresher courses both within and outside the country focused on their respective areas of expertise, allowing them to strengthen and rigor their military profession. This is evidenced by personal achievements that transcend the institutional and, of course, the national sphere. With this in mind, below are details of two Colombian Aerospace Force officers, one of a higher rank and the other of a lower rank, who have received important recognition.

|

Figure 4. Officials of the institution distinguished for their achievements |

|

|

Source: own elaboration

Note: the figure appears in its original language

Brigadier General Pedro Arnulfo Sánchez Suárez, for his career, work, and leadership, has been awarded three Medals of Valor and one Medal of Public Order, as well as other military and civilian decorations. The Brigadier General has developed a deep attachment to the Nation, to which he has made enormous contributions, working on important projects such as the development of the Night Vision Operation Manual, the development of the CACOM-5 Command and Control, Communications, Intelligence, and Information Technology Center, the structuring and development of the FAC's Basic Operational and Tactical Doctrine, and the structuring and development of the ARPIA IV attack helicopter. In addition, he has written various articles on doctrine and leadership for national and international journals. He was the commander of Operation Hope, which led to the discovery and rescue of four indigenous children lost in the Colombian jungle 40 days after the crash of plane HK2803 on May 1, 2023.

Lieutenant Yeimy Nataly Buitrago Leiva is the first Colombian woman to receive the Amelia Earhart Scholarship, awarded by the Zonta International Foundation. This scholarship is awarded to only 35 women internationally from all universities, who are selected based on their academic and research profiles, as well as the development and impact of their research proposals. She was a member of one of the expert panels for the Space4Women event, organized by the United Nations (in Daejeon, South Korea), which brings together various international experts in aerospace.

Military education should incorporate programs that promote a culture of peace and reconciliation. Teaching peaceful conflict resolution, the importance of dialogue and cooperation, and respect for diversity are essential components for preventing the resurgence of violence. Instilling these values in the military contributes to building a more peaceful society.

CONCLUSIONS

Military education is an essential component of a country's security and defense. Through the training of competent leaders, technological modernization, and the promotion of values and discipline, military education strengthens a nation's strategic and tactical capabilities. Its impact extends beyond the military sphere, contributing to national and international security and fostering peace and global cooperation. Therefore, investing in robust military education is essential for any country that aspires to maintain its security and defend its sovereignty.

In order to talk about education in the military, it is important to know the role they play in society, which is framed within a constitutional mission. The Armed Forces have been created for the security and defense of the State, and in that order, understanding the reasons for their rigorous training is vitally important so that it is not blurred or limited to the use of weapons. FAC officers are professionals who receive comprehensive training and the opportunity to pursue postgraduate studies based on institutional or individual interests. Their training transcends the cognitive level and contributes to strengthening military values and principles.

REFERENCES

Acero, C. y Machuca, D. (2021). The substitution program on trial: progress and setbacks of the peace agreement in the policy against illicit crops in Colombia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103158

Amoroso, J., Arciniegas, A., y González, L. (2023). Más allá de la seguridad pública: la militarización de la política democrática en América Latina. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 48(2), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/08263663.2023.2190654

Arias, F. (2020). Las elecciones de 1970 en la memoria. Señal memoria. https://www.senalmemoria.co/articulos/las-elecciones-de-1970-en-la-memoria

Barrera, V., López, M., Staples, H., y Kanai, M. (2022). From local turn to space-relational analysis: Participatory peacebuilding in a Colombian borderland. Political Geography, 98, 102729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102729

Bernal, O., Garcia-Betancourt, T., León-Giraldo, S., Rodríguez, L., y González-Uribe, C. (2024). Impact of the armed conflict in Colombia: Consequences in the health system, response and challenges. Conflict and Health, 18(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00561-6

Boulanger, S. (2022). ¡Zapatero, a tus zapatos! Explaining the social engagement of M-19 ex-combatants in education and social work institutions in Colombia. Third World Quarterly, 43(4), 760–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.2022979

Camargo, G., Sampayo, A., Peña, A., ... y Feged-Rivadeneira, A. (2020). Exploring the dynamics of migration, armed conflict, urbanization, and anthropogenic change in Colombia. PLOS ONE, 15(11), e0242266. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242266

Cárdenas, M. (2023). Why peacebuilding is condemned to fail if it ignores ethnicization. The case of Colombia. Peacebuilding, 11(2), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2022.2128583

Carrillo, C. (2020). Diseño de un modelo de vigilancia tecnológica como herramienta para mejorar las capacidades de las Fuerzas Armadas del Ecuador enfocado a la seguridad y defensa. [Trabajo de grado]. Universidad de las fuerzas armadas. https://repositorio.espe.edu.ec/bitstream/21000/22556/1/T-ESPE-043873.pdf

Crecente, F., Sarabia, M. y del Val, M. (2021). The hidden link between entrepreneurship and military education. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 163, 120429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120429

Culma, P., y Tatiana, K. (2021). Política Pública de Seguridad y Defensa Nacional–narrativas en disputa: Influencia de las narrativas sobre el conflicto armado con las FARC-EP en los cambios de la Política Pública de Seguridad y Defensa Nacional 2002-2020. [Tesis de grado]. Universidad Nacional https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/83518

Elston, C. (2020). Nunca Invisibles: Insurgent Memory and Self-representation by Female Ex-combatants in Colombia. Wasafiri, 35(4), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2020.1800254

Fernandez-Osorio, A., Miron, M., Cabrera-Cabrera, L., Corcione-Nieto, M. y Villalba-Garcia, L. (2023). Towards an effective gender integration in the armed forces: The case of the Colombian Army Military Academy. World Development, 171, 106348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106348

Figueroa, E. (2023). Propuesta de Directorio de Revistas Científicas de Seguridad y Defensa Nacional recuperadas desde Scopus y Scimago Journal, CAEN-EPG, Enver Vega. https://www.aacademica.org/enver.vega.figueroa/3

Georgi, F. (2022). Peace through the lens of human rights: Mapping spaces of peace in the advocacy of Colombian human rights defenders. Political Geography, 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102780

Gutiérrez, J., y Murphy, E. (2023). The unspoken red-line in Colombia: Gender reordering of women ex-combatants and the transformative peace agenda. Cooperation and Conflict, 58(2), 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/00108367221099085

Holmes, J., Palao, A., Callenes, M., Silva, N., y Cardenas, A. (2023). Attacking the grid: Lessons from a guerrilla conflict and efforts for peace in Colombia: 1990–2018. International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection, 42, 100621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcip.2023.100621

Jenne, N. (2020). The value of security cooperation in Sino–South American relations. Asian Education and Development Studies, 10(3), 433-444. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-08-2019-0121

Jiménez, S. (2020). Análisis comparativo del servicio militar en Colombia y otros países. http://hdl.handle.net/10654/37035

Lemon, L., y Hayes, J. (2020). Enhancing Trustworthiness of Qualitative Findings: Using Leximancer for Qualitative Data Analysis Triangulation. The Qualitative Report, 25(3), 604–614. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4222

Li, J., Xi, T. y Yao, Y. (2020). Empowering knowledge: Political leaders, education, and economic liberalization. European Journal of Political Economy, 61, 101823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2019.101823

Mohr, S., Sørensen, B., y Weisdorf, M. (2021). The Ethnography of Things Military – Empathy and Critique in Military Anthropology. Ethnos, 86(4), 600–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2019.1687553

Naranjo-Valencia, J., Ocampo-Wilches, A., y Trujillo-Henao, L. (2022). From Social Entrepreneurship to Social Innovation: The Role of Social Capital. Study Case in Colombian Rural Communities Victim of Armed Conflict. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 13(2), 244–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2020.1770317

Natow, R. (2020). The use of triangulation in qualitative studies employing elite interviews. Qualitative Research, 20(2), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119830077

Niño, C., y Palma, D. (2023). Transforming conflict and transforming violence: Determinants in the geometry of violence in Colombia. Critical Studies on Security, 11(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2023.2238999

Pérez, A., Sánchez, V. y Gómez, C. (2023). Representaciones sociales de un grupo de excombatientes sobre el cumplimiento del Acuerdo de Paz. Pensamiento Americano, 16(31), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.21803/penamer.16.31.651

Pineda, P., y Celis, J. (2022). Rejection and mutation of discourses in curriculum reforms: Peace education(s) in Colombia and Germany. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 54(2), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2021.1904006

Prem, M., Saavedra, S. y Vargas, J. (2020). End-of-conflict deforestation: Evidence from Colombia’s peace agreement. World Development, 129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104852

Sørensen, B., y Weisdorf, M. (2021). Awkward Moments in the Anthropology of the Military and the (Im)possibility of Critique. Ethnos, 86(4), 632–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2019.1688373

Vélez-Torres, I., y Méndez, F. (2022). Slow violence in mining and crude oil extractive frontiers: The overlooked resource curse in the Colombian internal armed conflict. The Extractive Industries and Society, 9, 101017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2021.101017

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the support received by Mrs. MY Ivette Zarur Valderrama, head of the Master's Program in Aeronautical Military Sciences and the Colombian Aerospace Force, for the information shared for the development of this research.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Data curation: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Formal analysis: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Fund acquisition: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Research: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Methodology: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Project administration: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Supervision: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Writing - original draft: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Rafael Andrés Gómez Jaramillo and Zully Ximena Rojas Ortiz.