doi: 10.58763/rc2024333

Scientific and Technological Research Article

Social extermination in the El Paraíso neighborhood. A structural constructivist analysis in the period 2010-2021

Exterminio social en el barrio El Paraíso. Un análisis constructivista estructural en el periodo 2010-2021

Ingrid Johanna Salas Ampudia1 ![]() *, Natalia Helena Álvarez1

*, Natalia Helena Álvarez1 ![]() *

*

ABSTRACT

The article explores the results of the project “Social Extermination in the El Paraíso neighborhood: 2010 - 2021”, carried out by the seedbed Esperanza en Marcha of the Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios - UNIMINUTO, Bogotá headquarters. The research focused on reflecting on the social representations of young people in the Paraíso neighborhood about the practices of social extermination that have occurred during the last ten years, based on the analysis of the categories, using the approaches of Pierre Bourdieu’s structural constructivism and a qualitative methodology of narrative cut, where information gathering techniques related to semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and social cartographies were used. The research revealed the structural components of social extermination, recognizing that it originates from dominance over the youth of the neighborhood through the establishment of practices and thoughts that seek to annihilate what is different, what does not fit into the capitalist, patriarchal, and colonial system, Recognizing that this generates some affectations in the construction of identity of the young people due to the stigmatization of their place of residence and the violation of their human rights, the above is also reflected in the absence of governmental accompaniment, where finally it is the scenarios of youth resistance that make visible the situations and demand protection from community actions.

Keywords: collective human rights, peace, resistance to oppression, violation of human rights.

JEL Classification: L83, M54, Z00

RESUMEN

El artículo explora los resultados del proyecto “Exterminio Social en el barrio El Paraíso: 2010-2021”, realizado desde el semillero Esperanza en Marcha, de la Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios (UNIMINUTO), sede Bogotá. La investigación se centró en reflexionar sobre las representaciones sociales de los jóvenes del barrio El Paraíso, frente a las prácticas de exterminio social ocurridas durante los últimos 10 años; eso a partir del análisis de categorías, los planteamientos del constructivismo estructural y una metodología cualitativa de corte narrativo, en la que se utilizaron técnicas de recolección de información relacionadas con entrevistas semiestructuradas, grupos focales y cartografías sociales. La investigación reveló los componentes estructurales del exterminio social, al reconocer que se origina desde un dominio sobre las juventudes del barrio, a través del establecimiento de prácticas y pensamientos que buscan aniquilar lo diferente o no encaje en el sistema capitalista, patriarcal y colonial; cosa que genera unas afectaciones en la construcción de identidad de los jóvenes por la estigmatización de su lugar de residencia y la vulneración a sus derechos humanos. Lo anterior se refleja en la ausencia de acompañamiento gubernamental, y en que son los escenarios de resistencia juvenil los que visibilizan las situaciones y exigen protección desde acciones comunitarias.

Palabras clave: derechos humanos colectivos, paz, resistencia a la opresión, violación de los derechos humanos.

Clasificación JEL: L83, M54, Z00

Received: 13-03-2024 Revised: 01-06-2024 Accepted: 15-06-2024 Published: 01-07-2024

Editor:

Carlos Alberto Gómez Cano ![]()

1Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios. Bogotá, Colombia.

Citar como: Salas, I. y Álvarez, N. (2024). Exterminio social en el barrio El Paraíso. Un análisis constructivista estructural en el periodo 2010-2021. Región Científica, 3(2), 2024333. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2024333

INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of "Social Cleansing," as the communities know it, is a targeted social extermination that, according to the history of Ciudad Bolívar, is directly attributed to the paramilitary groups that inhabit the various neighborhoods. However, in recent years, it has been revealed that the residents of the area themselves actively participate in this process, organizing groups and carrying out the murders under the guise of improving security.

From this, questions arise surrounding the acts of social extermination in the El Paraíso neighborhood, which have an intimate character, as it is a social problem that is being investigated due to its proximity to the neighborhood, as it is located in the area where one of the researchers resides. The project is guided by a structural constructivist approach, allowing for the identification of the issues that originate and foster the development of the problem. It also explores the subjective elements condensed in the social representations of the neighborhood's youth. This fosters critical and proactive inquiry into the strategies of neighborhood foundations and leaders seeking to denounce and definitively eliminate the practice of Social Extermination in the area.

Therefore, it allows for constructing critical and reflective knowledge around the social reality addressed and its relationship with the constituent elements of violence, as the annihilation of differences. The research focuses specifically on the Human Rights subfield, which makes visible the events that occurred within the framework of the practices of social extermination in the El Paraíso neighborhood, as well as recognizing the processes of defense and resistance of some youth organizations in the area.

METHODOLOGY

Qualitative design

The research methodology used was qualitative, based on the narrative method. Considering that young people construct their practices through the meanings they give to social phenomena, the stories constructed with the participants demonstrate the relevance and impact on the daily life of Social Extermination events between 2010 and 2021. The narrative method allowed for the expression of detailed information in time, space, and impacts; it also showed that narrative can be a reliable and clear path to producing knowledge about the social world (María & Ortiz, 2021).

The research was based on Bourdieu's structuralist constructivist approach (Jacay, 2022; Hernández, 2022), as it addresses the central elements of "campus" and "habitus," contextualized within the territorial dynamics of the El Paraíso neighborhood. The central categories that guided the analysis were social representations, social extermination, and resistance, from the perspective of the authors Rojas (2022) and Cote and Vega (2022), among others.

Context and sample

The level of study is descriptive in scope, describing situations or events occurring in the area and, to a certain extent, developing a social representation of the phenomenon of Social Extermination in the El Paraíso neighborhood. This is based on the exploration of the social representations of 12 young people belonging to grassroots social organizations who carry out resistance operations against acts of violence and defend human rights through collective actions. To collect this information, 12 structural interviews were conducted with youth leaders, a social mapping was conducted with a group of young people that included a tour of the neighborhood to encourage the exercise of remembrance and memory, and three focus groups were held to delve deeper into issues related to social representations regarding social extermination and resistance actions.

Systematic review design

For the bibliographic review, the guidelines of Sánchez et al. (2023) were followed, which were adapted to this specific article. A search was carried out through the Scopus database, taking into account the thematic descriptors “social representations” AND “young”. Initially, the search patterns established were original and review articles in English or Spanish published between 2021 and 2024. Likewise, 35 publications were identified in a total of 32 journals, as shown in table 1; of these, 30 belonged to quartile 1 and the rest (2) to quartile 2; 19 were from the United Kingdom, 8 from the Netherlands, 4 from the United States, and 1 from China. The areas of knowledge represented were Social Sciences (29), Earth Sciences (6), Medical Sciences (5), Computer Sciences (4), Business Sciences (3), and other sciences (3). Most journals were not limited to a specific area of knowledge but linked two or more. The frequency of publications by year was as follows: 2021 (4), 2022 (9), 2023 (15), and 2024 (7).

|

Table 1. Analysis of the sources consulted in the Scopus database |

||||

|

Title of the magazine |

Country |

Area of knowledge |

H-index |

Quartile |

|

International Journal of Educational Research |

United Kingdom |

Social Sciences |

15 |

Q1 |

|

International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks |

China |

Earth Sciences Social Sciences |

19 |

Q1 |

|

Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology |

Netherlands |

Social Sciences |

9 |

Q2 |

|

Children and Youth Services Review |

United Kingdom |

Social Sciences |

115 |

Q1 |

|

Journal of Environmental Management |

United States |

Environmental Sciences Medicine |

243 |

Q1 |

|

International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction |

United Kingdom |

Earth Sciences Social Sciences |

86 |

Q1 |

|

Health & Place |

United Kingdom |

Medicine Social Sciences |

137 |

Q1 |

|

Advances in Life Course Research |

Netherlands |

Social Sciences |

47 |

Q2 |

|

Current Research in Environmental Sustainability |

Netherlands |

Environmental Sciences |

18 |

Q1 |

|

Social Science & Medicine |

United Kingdom |

Social Sciences Medicine |

283 |

Q1 |

|

International Journal of Intercultural Relations |

United Kingdom |

Business Sciences Social Sciences |

102 |

Q1 |

|

Appetite |

United States |

Nursing Social Sciences |

178 |

Q1 |

|

Learning, Culture and Social Interaction |

Netherlands |

Social Sciences |

35 |

Q1 |

|

Computers in Human Behavior Reports |

United Kingdom |

Computer Science Social Sciences |

22 |

Q1 |

|

Tourism Management |

United Kingdom |

Business Sciences Social Sciences |

255 |

Q1 |

|

International Journal of Drug Policy |

Netherlands |

Medicine |

98 |

Q1 |

|

SSM - Mental Health |

United Kingdom |

Social Sciences |

11 |

Q1 |

|

Energy Research & Social Science |

United Kingdom |

Energy Social Sciences |

113 |

Q1 |

|

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology |

United States |

Social Sciences |

171 |

Q1 |

|

Social Sciences & Humanities Open |

United Kingdom |

Social Sciences |

25 |

Q1 |

|

Child Abuse & Neglect |

United Kingdom |

Medicine Social Sciences |

174 |

Q1 |

|

Computers in Human Behavior |

United Kingdom |

Social Sciences Computer Science |

251 |

Q1 |

|

Wellbeing, Space and Society |

Netherlands |

Social Sciences |

9 |

Q1 |

|

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology |

United States |

Social Sciences |

171 |

Q1 |

|

Journal of Rural Studies |

United Kingdom |

Biological Sciences Social Sciences |

135 |

Q1 |

|

SSM - Qualitative Research in Health |

United Kingdom |

Social Sciences |

9 |

Q1 |

|

Global Environmental Change |

United Kingdom |

Environmental Sciences Social Sciences |

225 |

Q1 |

|

Women's Studies International Forum |

United Kingdom |

Social Sciences |

71 |

Q1 |

|

International Journal of Information Management |

United Kingdom |

Business Sciences Computer Science Social Sciences |

177 |

Q1 |

|

Computers in Human Behavior |

Netherlands |

Social Sciences Computer Science |

251 |

Q1 |

|

Travel Behaviour and Society |

Netherlands |

Social Sciences |

46 |

Q1 |

|

Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions |

Netherlands |

Environmental Sciences Social Sciences |

79 |

Q1 |

|

Source: own elaboration, based on data extracted from https://www.scimagojr.com/ |

||||

Among the sources consulted, the authors addressed social representations among young people from different perspectives. In all cases, factors were identified that influenced individuals or groups, causing marginalization, rejection, or violence, such as criticism, identity, type of employment, gender perspective, religion, health, habitat, Internet access, social practices, race, and religion, as shown in table 2.

|

Table 2. Distribution of authors according to the treatment they offer to social representations in young people |

||

|

Authors |

Year |

Treatment of social representations |

|

Alkhateeb, H., Romanowski, M., Chaaban, Y., and Abu-Tineh, A. |

2022 |

Gender approach |

|

Blanco-Fuente, I., Ancín, R., Albertín-Carbó, P., and Pastor, Y. |

2024 |

|

|

Miele, C., Maquigneau, A., Joyal, C., Bertsch, I., Gangi, O., Gonthier, H., Rawlinson, C., Vigourt-Oudart, S., Symphorien, E., Heasman, A., Letourneau, E., Moncany, A.-H., and Lacambre, M. |

2023 |

|

|

Salgado, F., and Magalhães, S. I. |

2024 |

|

|

Buchan, P., Evans, L. S., Barr, S., and Pieraccini, M. |

2024 |

Profession, identity and employment |

|

Cvetković, V., Dragašević, A., Protić, D., Janković, B., Nikolić, N., and Milošević, P. |

2022 |

|

|

Lahlou, S., Heitmayer, M., Pea, R., Russell, M., Schimmelpfennig, R., Yamin, P., Dawes, A., Babcock, B., Kamiya, K., Krejci, K., Suzuki, T., and Yamada, R. |

2022 |

|

|

Rault-Chodankar, Y.-M. |

2022 |

|

|

Blanchard, C., and Paquet, M. |

2023 |

|

|

Holder, A., Ruhanen, L., Walters, G., and Mkono, M. |

2023 |

Psychology |

|

Holm, S., Petersen, M., Enghoff, O., and Hesse, M. |

2023 |

|

|

Hosny, N., Bovey, M., Dutray, F., and Heim, E. |

2023 |

|

|

Kazarovytska, F., and Imhoff, R. |

2023 |

|

|

Larrea, C., Muñoz, A., Echeverría, R., Larrea, O., and Gracia-Arnaiz, M. |

2024 |

|

|

Selzer, S., and Lanzendorf, M. |

2022 |

|

|

Julsrud, T., and Aasen, M. |

2024 |

Artificial intelligence |

|

Millet, K., Buehler, F., Du, G., and Kokkoris, M. |

2023 |

|

|

Savela, N., Oksanen, A., Pellert, M., and Garcia, D. |

2021 |

|

|

Scales, D., Gorman, J., DiCaprio, P., Hurth, L., Radhakrishnan, M., Windham, S., Akunne, A., Florman, J., Leininger, L., and Starks, T. |

2023 |

|

|

Birman, D. |

2024 |

Social and environmental context |

|

Gago, T., and Sá, I. |

2021 |

|

|

Rostan, J., Billing, S.-L., Doran, J., and Hughes, A. |

2022 |

|

|

Valor, C., Martino, J., and Ruiz, L. |

2023 |

|

|

Fannin, M., Collard, S., and Davies, S. |

2024 |

Health and gender |

|

Fuster, N., Palomares-Linares, I., and Susino, J. |

2023 |

Crisis |

|

Gaspar, M., Sato, P., and Scagliusi, F. |

2022 |

Health |

|

Gesthuizen, M., Savelkoul, M., y Scheepers, P. |

2021 |

Religion |

|

Graça, J., Campos, L., Guedes, D., Roque, L., Brazão, V., Truninger, M., and Godinho, C. |

2023 |

Nutrition |

|

Grossen, M., Zittoun, T., and Baucal, A. |

2022 |

Education |

|

Harren, N., Walburg, V., and Chabrol, H. |

2021 |

Addictions |

|

Mbaye, A., Schmidt, J., and Cormier-Salem, M. |

2023 |

Social practices |

|

Moore, G., Fardghassemi, S., and Joffe, H. |

2023 |

Loneliness and citizenship |

|

Mosley, A., Biernat, M., and Adams, G. |

2023 |

Racism |

|

Phillips, M., Smith, D., Brooking, H., and Duer, M. |

2022 |

Gentrification |

|

Robert, S., Quercy, A., and Schleyer-Lindenmann, A. |

2023 |

Territoriality |

|

Source: own elaboration |

||

Using Lens.org software, 98 additional sources extracted from the Scopus and Web of Science databases were processed. The subject descriptors used to identify the sources were: "social representations" AND "young". The search was conducted based on the period (2021-2024) and document type (journal article or book chapter).

The research results are presented in line with the objectives set forth in the study. At a general level, it can be stated that the social representations constructed by young people around the acts of social extermination in the El Paraíso neighborhood expressed their feelings about it, indicating that—from these acts onward—the struggle to survive in a society that violates, stigmatizes, and marginalizes them due to their social and geographical location constantly grows. Bourdieu refers to them as the environment where social actors are governed by their experiences, customs, and conceptions derived from social domination.

|

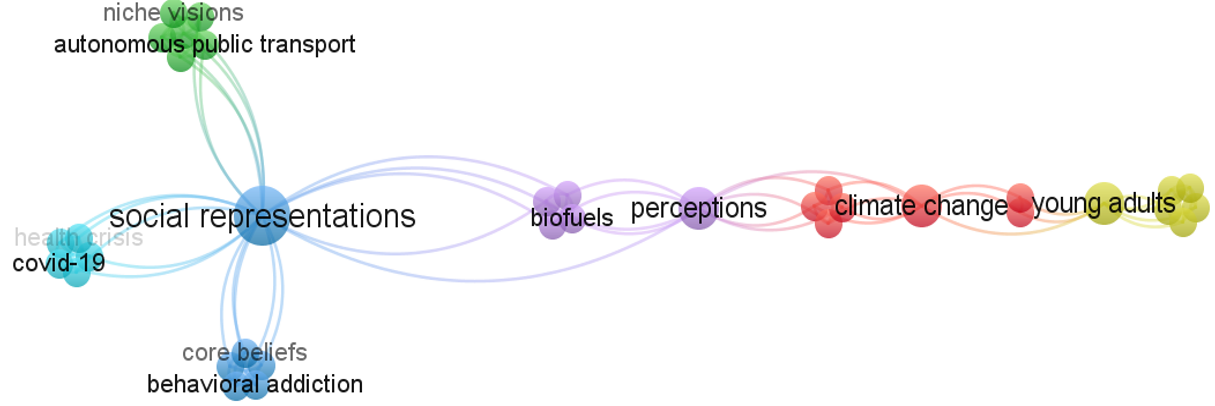

Figure 1. Evidence of the keyword co-occurrence network |

|

|

Source: own elaboration based on VOSviewer software

Based on these data, the following table shows the analysis of research clusters associated with social representations in young people, based on the items.

|

Table 3. Cluster analysis |

|||

|

Cluster |

Items |

Color |

Description |

|

C1 |

7 |

Red |

Focuses on environmental aspects |

|

C2 |

6 |

Green |

Focuses on social expectations and business opportunities |

|

C3 |

6 |

Dark blue |

Focuses on behaviors, addictions, and issues associated with internet use |

|

C4 |

6 |

Mustard |

Focuses on deprivation, loneliness, social connections, and neighborhood |

|

C5 |

5 |

Purple |

Focuses on productive aspects |

|

C6 |

5 |

Light blue |

Focuses on issues associated with COVID-19, such as isolation |

|

Total |

35 |

||

Source: own elaboration based on data processed with the VOSviewer software

Analysis of the sources consulted through Lens.org allowed us to determine trends in academic work over time (2021-2024), areas of knowledge, main journals, and countries with the highest frequency of publications on social representations and youth.

|

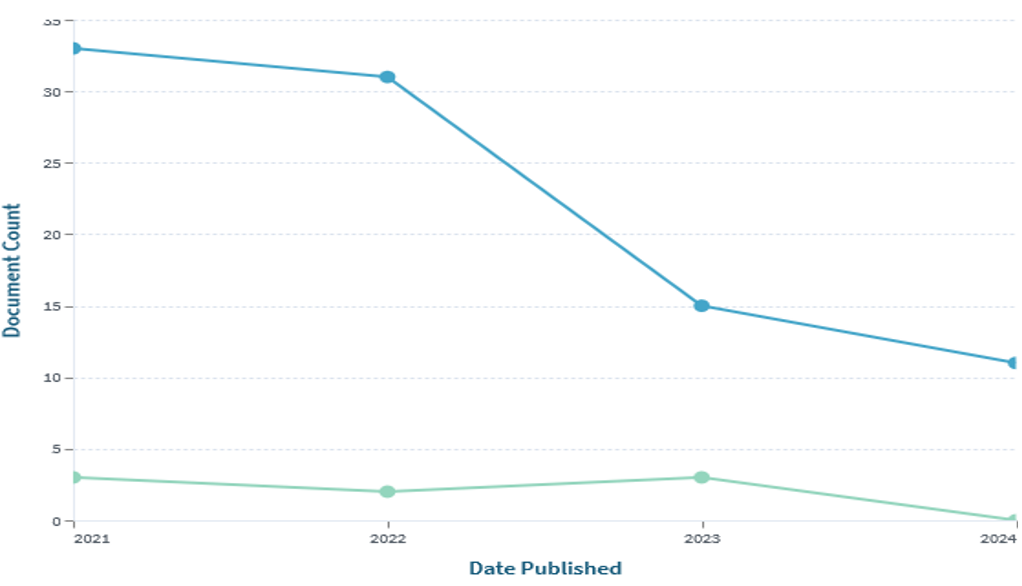

Figure 2. Academic papers over time |

|

|

Source: own elaboration based on Lens.org software

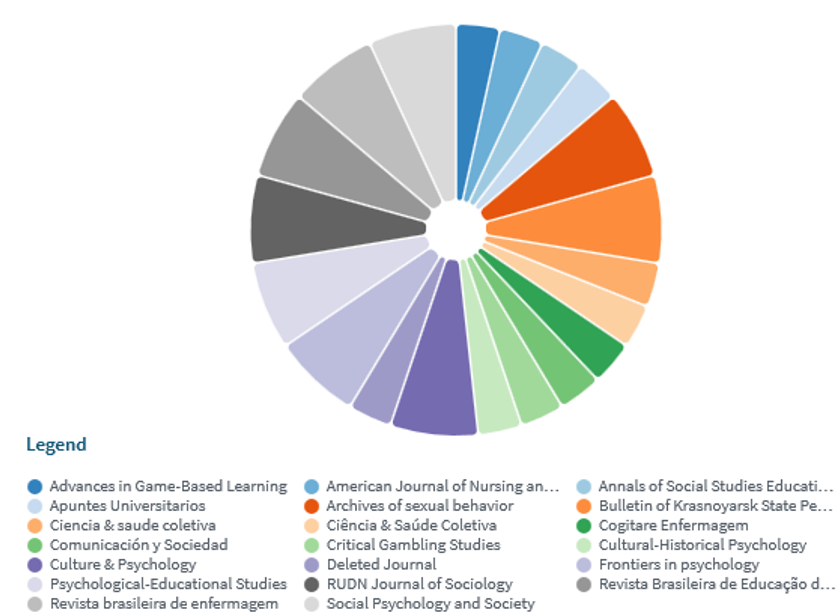

This topic has been addressed from different areas of knowledge; figure 3 shows the variety of these. It is notable how general areas of knowledge are illustrated, but most are specific and diverse. This allows us to determine the variety and transversality of these categories (social representations and youth).

|

Figure 3. Main areas of knowledge |

|

|

Source: own elaboration based on Lens.org software

The trend in the number of articles per journal is between 1 and 3 per year and there is a great variety of these, as shown in figure 4.

|

Figure 4. Main journals |

|

|

Source: own elaboration based on Lens.org software

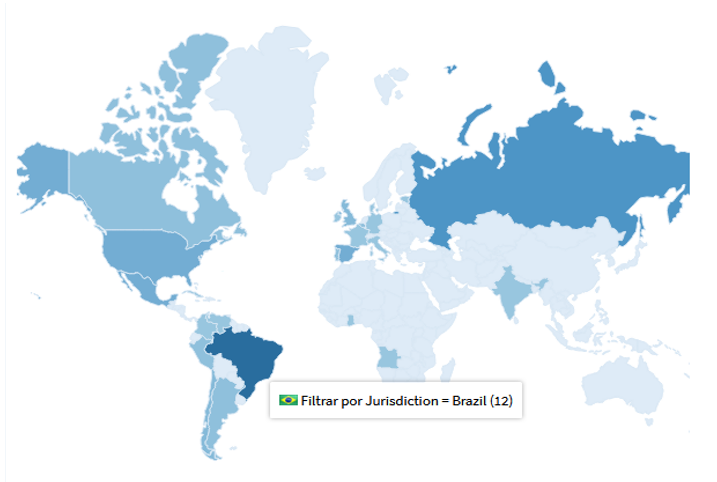

The country with the largest number of publications on the topic is Brazil, with 12 articles. With the exception of Russia, the region with the largest number of publications on the topic is the Americas, with a similarity across countries (figure 5).

|

Figure 5. Most active countries |

|

|

Source: own elaboration based on Lens.org software

The literature review reveals that in Ciudad Bolívar, acts of social extermination date back to 1983 when it began to emerge as a peripheral locality of Bogotá (Caquimbo, 2023; Fajardo, 2024; Guaman, 2024; Orjuela & Urrego, 2024). Indeed, the locality continues to bear the consequences of the city's social inequality, becoming a contested territory where various armed groups maintain territorial control, violating the human rights of its inhabitants.

Based on the reconstruction of the acts of social extermination recognized by young people in the El Paraíso neighborhood over the past 10 years, a timeline was collaboratively developed, establishing that since 2010, several events have occurred that have impacted the neighborhood, such as the creation of micro-trafficking gangs and the arrival of BACRIM (Basque Drug Trafficking Units) between 2010 and 2011; The identification of "social cleansing" as a systematic practice of these groups, recalling anecdotes of the death and disappearance of several well-known young people in the neighborhood, with a peak between 2012 and 2015; the progressive appearance of pamphlets signed by the illegal organization "Águilas Negras" and an increase in extermination cases between 2015 and 2019, with an increase in murders of community leaders and human rights defenders in areas of the neighborhood between 2019 and 2022.

To this extent, it is identified that the practice of social extermination experienced in the El Paraíso neighborhood has influenced the lifestyles of young people in relation to the increase in stigma, inequality, and rejection of youth identity. This indicates an exercise in camouflaging these practices, based on discourses of citizen security, which entails the decision to "do justice" violently and by one's own hand, even if it is through illegal armed groups. Just as there are pressure groups on these young people, there are established social structures that can serve as a catalyst, such as the family, the school, the community, projects, foundations, and NGOs (Peñate & Jiménez, 2020; Aloulou, 2022).

The above, in the authors' opinion, prevents young people from developing freely, even causing them to fail to reach adulthood, leaving them without options. This violence has no repercussions for the perpetrators, as cases are recorded as homicides and do not lead to an effective resolution regarding the identification of the individual or group perpetrators involved. It causes emotional pain and frustration for family, friends, and community members.

It could be said that the violence experienced today negatively affects young people in aspects such as mental health, behavior, interaction, and personal, intrapersonal, and interpersonal relationships with others and their environment in the face of these changes. They are exposed to a difficult reality to face, which has given rise to discrimination, hatred, contempt, and resentment over the years. Social extermination is based on domination and death, causing the community to subject young people to rules established years ago, even though these rules may be repressive, coercive, and violent. These behaviors can be modeled in formal or informal educational contexts, according to Cristancho (2023), which include schools, neighborhood initiatives, creative workshops, social integration and addiction relief initiatives, health promotion, and social prevention, among others.

The social representations of social extermination that young people have constructed deprive people of their lives; this is part of symbolic violence when it is perpetrated out of ridicule, mockery, or to send a message to the other citizens of the victim. This has been on the rise, especially in Colombia, as a consequence of conflicts and social problems and dysfunctional individuals who practice social extermination, impacting young people increasingly.

Finally, the human rights advocacy processes being carried out in the El Paraíso neighborhood in response to territorial transformation are led by grassroots social organizations, including the Nuguesi Foundation, the Youth Center, the "Night Has a Thousand Eyes, the Day Only One" initiative, and "Survamos," among others. It is a priority to reflect on and build new systems of "practices of self," as Foucault put it, according to Luzuriaga et al. (2022), or to modify conventional and culturally established practices in order to generate new practices and, therefore, new forms of subjectivation, which offer young people alternative futures so they are not forced into the violence experienced in the El Paraíso neighborhood. In line with Cardo et al. (2023), the community, rather than exerting pressure on young people to alienate them, is the ideal space to foster respect for cultural diversity, a sense of belonging, identity, and self-esteem.

The stigma of neighborhoods, society, and the disastrous dominant social order of paramilitary groups leads some young people to think about what social extermination represents, and this attitude is acquired as a framework for their lives. Therefore, community organizations and collective unity are essential in searching for processes that encourage and allow young people to participate in art, music, and sports settings to foster the neighborhood's territorial identity. An example of this is young people who express their struggle against environmental pollution and crime through murals, graffiti, and expressions that mark their territorial identity and feelings (Mora & Camacho, 2023; Cruz et al., 2024).

In this sense, public spaces constitute settings that, in addition to serving as leisure and enjoyment, foster social exchange and facilitate community dynamism. Young people frequently appropriate these spaces for recreational purposes but also for the formation of identities, exchange of ideas, and expressions. This demonstrates the existence of a geographic, spatial, and belonging identity (Cote & Vega, 2022). Therefore, there is a constant struggle for life, hope, and youth dignity; through this approach, leaders and foundations are joining forces to create alternatives that connect young people with recreational, artistic, or employment activities.

The Youth Center is one example of how young people are integrated through projects and engage in sports, recreational, and artistic activities, such as dance, theater, urban music, visual arts, writing, and photography. These types of activities foster entrepreneurship, creativity, social participation, and training. They give young people a real role to play, catering to their tastes and preferences (Almeida, 2021).

Youth movements emerge through the organizations structured in Ciudad Bolívar as sociocultural processes. They connect with educational and employment alternatives, where they are accepted as key players in political action, a fundamental part of the resistance movement due to the different conditions in which they find themselves. The social movement constitutes the fundamental axis of community work based on popular participation and motivates the mobilization of individuals and their organizations, which leads to the fight for rights, the increase of state presence, and the diversification of efforts to rebuild the social fabric in the locality (Rojas & Quintana, 2022), in order to promote the comprehensive development of individuals, with participatory and equitable democracy.

Given the current situation in the sector, it is pertinent to support and contribute to solutions focused on Human Rights, comprehensive government strategies, and participatory public policies that recognize the experiences of the youth population excluded and discriminated against by illegal groups. At the same time, it is necessary to raise awareness among society at large, including public servants, community leaders, and others, in the face of a phenomenon that does not completely change but rather mutates over the years. This is done in order to overcome the social paradigm, negative stereotypes, the fractured identity, and the false beliefs that justify violence and techniques of social extermination.

Society at large must commit to denaturalizing the acts of social extermination occurring throughout the country, and it is a priority to advance effective processes to defend life based on initiatives from the communities themselves. Based on their experience, they recognize those actions that can lead to strengthening bonds based on affection, empathy, and collective interests while also demanding institutional responses translated into public policies that prevent, mitigate, and put an end to these acts, using a cross-cutting approach. This is even more so when means of coexistence are required to maintain relationships among young people based on mutual recognition and building on differences.

It is important to highlight that Bourdieu's concepts of "campus" and "habitus" allow us to recognize the complexity of social extermination, based on social structures independent of consciousness and will, in which groups exercise dominance and power that guide the community, permeating its differences and similarities through capital. In short, young people are bound to this structure, as they cannot renounce life in society; the former conditions the individual's subjective constructions, limiting and directing them. Furthermore, this structure generates psychosocial effects on young people that force them to adopt patterns of action in the face of practices of social extermination, and social movements are effective in this regard. These do not necessarily have to provoke rebellion and opposition; they can also be led toward the search for educational, welfare, health, environmental, and economic improvements (Lučić et al., 2021).

For all these reasons, we must continue to address the structural notion of social extermination, which allows us to interpret the facts systematically rather than in isolation. It leads to the generation of situated knowledge that fosters the identification, formulation, and implementation of concrete actions to mitigate, counteract, and reject social extermination in the local community, not only through community demands but also through the defense of human rights at the local level.

CONCLUSIONS

Social representations play a crucial role in young people's perceptions of their environment and their place in society. These can influence their attitudes toward human rights and social justice, as well as their place in their environment, community, or school and/or workplace. As agents of change, young people have the potential to challenge and transform these representations, especially in the context of practices of social extermination, which include systematic violence and the marginalization of certain groups, seriously violating human rights. Projects, foundations, NGOs, and other organizations that work in an integrated manner to address social gaps, address the problems young people face, and seek greater integration into society are important in this regard. It is essential that they are informed and engaged, recognizing the practices of social extermination, their consequences and causes, and dismantling the structures that sustain them. By promoting and defending human rights, young people can foster a culture of respect and dignity, becoming active advocates and agents of change in their communities, thus contributing to building a more just and inclusive society.

REFERENCES

Almeida, N. (2021). Engaging in politics through youth transitions. Journal og Youth Studies, 27(7), 921-938. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2023.2187281

Aloulou, W. (2022). The influence of institutional context on entrepreneurial intention: evidence from the Saudi young community. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 16(5), 677-698. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-02-2021-0019

Alkhateeb, H., Romanowski, M., Chaaban, Y., y Abu-Tineh, A. (2022). Men and classrooms in Qatar: A Q methodology research. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2022.100203

Birman, D. (2024). The history of natural resources management among the Luo society of Western Kenya: Socio-ecological parameters of landscape heterogeneity. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 12(2), 278-294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgeop.2024.04.002

Blanchard, C., y Paquet, M. (2023). Exploring environmental identity at work and at home: A multifaceted perspective. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 5, 100141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cresp.2023.100141

Blanco-Fuente, I., Ancín, R., Albertín-Carbó, P., y Pastor, Y. (2024). Do adults listen? A qualitative analysis of the narratives of LGBTQI adolescents in Madrid. Children and Youth Services Review, 161, 107613. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107613

Buchan, P., Evans, L., Barr, S., y Pieraccini, M. (2024). Thalassophilia and marine identity: Drivers of ‘thick’ marine citizenship. Journal of Environmental Management, 352, 120111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120111

Caquimbo, S. (2023). Poéticas del habitar en el borde informal de Bogotá: ocupar, construir, cultivar 'la Loma'. [Tesis de grado]. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/84444

Cardo, A., Valls, B., Gil, E. y Hernán, M. (2023). Propuestas para la orientación comunitaria de la atención primaria: identificar agentes clave para la formación. Gaceta Sanitaria, 37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2022.102269

Cote, G. y Vega, L. (2022). La noción de destrucción en el genocidio y la protección de la identidad cultural de grupos étnicos en conflictos armados: el caso del pueblo nasa en el norte del departamento del Cauca (Colombia). Díkaion, 31(2). https://doi.org/10.5294/dika.2022.31.2.7

Cristancho, G. (2023). Actitud e intención hacia el consumo responsable en los hogares de Bogotá. Tendencias, 24(1), 130-154. https://doi.org/10.22267/rtend.222302.218

Cruz, A., Herrera, L., Lara, S., Mora, A., y Camacho, I. (2024). Luchas y desarraigos por la tierra y resistencias juveniles por el derecho a la ciudad en el postconflicto: una mirada a la construcción de paz desde la periferia de Bogotá. Discimus. Revista Digital De Educación, 2(2), 21-46. https://doi.org/10.61447/20231211/art2

Cvetković, V., Dragašević, A., Protić, D., … y Milošević, P. (2022). Fire safety behavior model for residential buildings: Implications for disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 76, 102981. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102981

Fajardo, L. (2024). El cine: un sorbo de vida, los Derechos Humanos en el cine colombiano. Universidad Libre. https://hdl.handle.net/10901/28615.

Fannin, M., Collard, S., y Davies, S. (2024). Power, intersectionality and stigma: Informing a gender- and spatially-sensitive public health approach to women and gambling in Great Britain. Health & Place, 86, 103186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2024.103186

Fuster, N., Palomares-Linares, I., y Susino, J. (2023). Changes in young people's discourses about leaving home in Spain after the economic crisis. Advances in Life Course Research, 55, 100526. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2023.100526

Gago, T., y Sá, I. (2021). Environmental worry and wellbeing in young adult university students. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 3, 100064. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2021.100064

Gaspar, M., Sato, P., y Scagliusi, F. (2022). Under the ‘weight’ of norms: Social representations of overweight and obesity among Brazilian, French and Spanish dietitians and laywomen. Social Science & Medicine, 298, 114861. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114861

Gesthuizen, M., Savelkoul, M., y Scheepers, P. (2021). Patterns of exclusion of ethno-religious minorities: The ethno-religious hierarchy across European countries and social categories within these countries. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 82, 12-24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.03.001

Graça, J., Campos, L., Guedes, D., ... y Godinho, C. (2023). How to enable healthier and more sustainable food practices in collective meal contexts: A scoping review. Appetite, 187, 106597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.106597

Grossen, M., Zittoun, T., y Baucal, A. (2022). Learning and developing over the life-course: A sociocultural approach. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 37, 100478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100478

Guaman, M. (2024). Francisco Marcalla, el pionero del comercio en Pallatanga. Una interpretación desde la memoria colectiva. [Tesis de grado]. Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo. http://dspace.unach.edu.ec/handle/51000/12952

Harren, N., Walburg, V., y Chabrol, H. (2021). Validation study of the Core Beliefs about Behavioral Addictions and Internet Addiction Questionnaire (CBBAIAQ). Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, 100096. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100096

Hernández, M. (2022). Análisis de las literacidades digitales emergentes en la práctica docente remota de profesores universitarios desde el habitus docente. Caso Ibero Puebla. [Tesis de grado]. Universidad Iberoamericana de Puebla. http://repositorio.iberopuebla.mx/handle/20.500.11777/5485

Holder, A., Ruhanen, L., Walters, G., y Mkono, M. (2023). “I think … I feel …”: using projective techniques to explore socio-cultural aversions towards Indigenous tourism. Tourism Management, 98, 104778. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104778

Holm, S., Petersen, M., Enghoff, O., y Hesse, M. (2023). Psychedelic discourses: A qualitative study of discussions in a Danish online forum. International Journal of Drug Policy, 112, 103945. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103945

Hosny, N., Bovey, M., Dutray, F., y Heim, E. (2023). How is trauma-related distress experienced and expressed in populations from the Greater Middle East and North Africa? A systematic review of qualitative literature. SSM - Mental Health, 4, 100258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2023.100258

Jacay, A. (2022). Convivencia escolar y ciudadanía en estudiantes del nivel secundaria de la Institución Educativa 20955-2 “Naciones Unidas” de la provincia de Huarochirí, 2021. [Tesis de grado]. Universidad César Vallejo. https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/87590

Julsrud, T., y Aasen, M. (2024). “Robots taking over the world… fantastic!” Understanding social representations, familiarity and visions of experiments with autonomous public transportation. Energy Research & Social Science, 115, 103646. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2024.103646

Kazarovytska, F., y Imhoff, R. (2023). No differences in memory performance for instances of historical victimization and historical perpetration: Evidence from five large-scale experiments. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 105, 104440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104440

Lahlou, S., Heitmayer, M., Pea, R., … y Yamada, R. (2022). Multilayered Installation Design: A framework for analysis and design of complex social events, illustrated by an analysis of virtual conferencing. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 6(1), 100310. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100310

Larrea-Killinger, C., Muñoz, A., Echeverría, R., Larrea, O., y Gracia-Arnaiz, M. (2024). Trust and distrust in food among non-dependent elderly people in Spain. Study on socio-cultural representations through the analysis of cultural domains. Appetite, 197, 107306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2024.107306

Lučić, A., Uzelac, M. y Previšić, A. (2021). The power of materialism among young adults: exploring the effects of values on impulsiveness and responsible financial behavior. Young Consumers, 22(2), 254-271. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-09-2020-1213

Luzuriaga, E., Rios-Rivera, I. y Chiriboga, V. (2022). Una aproximación al género desde las relecturas de Butler y Connell en los liderazgos políticos femeninos en América Latina. IC: Revista Científica de Información y Comunicación, 19, 57-81. https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/141290

María, A. y Ortiz, R. (2021). La narrativa como un método para la construcción y expresión del conocimiento en la investigación didáctica, 16. SciELO Colombia. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1794-89322020000200183

Mbaye, A., Schmidt, J., y Cormier-Salem, M. (2023). Social construction of climate change and adaptation strategies among Senegalese artisanal fishers: Between empirical knowledge, magico-religious practices and sciences. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 7(1), 100360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100360

Miele, C., Maquigneau, A., Joyal, C., … y Lacambre, M. (2023). International guidelines for the prevention of sexual violence: A systematic review and perspective of WHO, UN Women, UNESCO, and UNICEF's publications. Child Abuse & Neglect, 146, 106497. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106497

Millet, K., Buehler, F., Du, G., y Kokkoris, M. (2023). Defending humankind: Anthropocentric bias in the appreciation of AI art. Computers in Human Behavior, 143, 107707. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107707

Moore, G., Fardghassemi, S., y Joffe, H. (2023). Wellbeing in the city: Young adults' sense of loneliness and social connection in deprived urban neighbourhoods. Wellbeing, Space and Society, 5, 100172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wss.2023.100172

Mora, A. y Camacho, I. (2023). Luchas y resistencias juveniles territoriales, una voz por la exigibilidad de derechos en El Recuerdo Sur y Los Alpes - Ciudad Bolívar. [Trabajo de grado]. Universidad de La Salle. https://ciencia.lasalle.edu.co/trabajo_social/989

Mosley, A., Biernat, M., y Adams, G. (2023). Sociocultural engagement in a colorblind racism framework moderates perceptions of cultural appropriation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 108, 104487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2023.104487

Orjuela, I., y Urrego, L. (2024). Secuencia didáctica: la incidencia de la violencia en el territorio, un acercamiento del conflicto armado con estudiantes de grado decimo de la IED María Mercedes Carranza. [Trabajo de grado]. Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Colombia. http://repository.pedagogica.edu.co/handle/20.500.12209/19934

Peñate, A. y Jiménez, G. (2020). La educación patrimonial en los miembros de la comunidad del Centro Histórico Urbano de Matanzas. ATENAS, 2(50), 66-84. https://atenas.reduniv.edu.cu/index.php/atenas/article/view/562

Phillips, M., Smith, D., Brooking, H., y Duer, M. (2022). The gentrification of a post-industrial English rural village: Querying urban planetary perspectives. Journal of Rural Studies, 91, 108-125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.02.004

Rault-Chodankar, Y. (2022). ‘We care… because care is growth’. The low-tech imaginaries of India's small-scale pharmaceutical enterprises. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health, 2, 100144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100144

Robert, S., Quercy, A., y Schleyer-Lindenmann, A. (2023). Territorial inertia versus adaptation to climate change. When local authorities discuss coastal management in a French Mediterranean region. Global Environmental Change, 81, 102702. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102702

Rojas, C. (2022). Emoterras del Estado-nación colombiano. https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=YR-cEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA15&dq=Carlos+Eduardo+Rojas&ots=Rl9F8m4fbE&sig=lSbG-eRq-__M4e4M_I-KXnjC3LU#v=onepage&q=Carlos%20Eduardo%20Rojas&f=false

Rojas, M. y Quintana, L. (2022). Sobre la primera y la última línea. Los vencidos de la historia y sus luchas por abrir el porvenir (Colombia, paro nacional, 2021). Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 47(3). 346-368. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08263663.2022.2110718

Rostan, J., Billing, S.-L., Doran, J., y Hughes, A. (2022). Creating a social license to operate? Exploring social perceptions of seaweed farming for biofuels in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Ireland. Energy Research & Social Science, 87, 102478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102478

Salgado, F., y Magalhães, S. (2024). “I am my own future” representations and experiences of childfree women. Women's Studies International Forum, 102, 102849. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2023.102849

Sánchez, Y., Pérez, A., Hernández, A., … y Rodríguez, E. (2023). Cultura hospitalaria y responsabilidad social: un estudio mixto de las principales líneas para su desarrollo. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología, 2(451). https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2023451

Savela, N., Oksanen, A., Pellert, M., y Garcia, D. (2021). Emotional reactions to robot colleagues in a role-playing experiment. International Journal of Information Management, 60, 102361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102361

Scales, D., Gorman, J., DiCaprio, P., … y Starks, T. (2023). Community-oriented Motivational Interviewing (MI): A novel framework extending MI to address COVID-19 vaccine misinformation in online social media platforms. Computers in Human Behavior, 141, 107609. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107609

Selzer, S., y Lanzendorf, M. (2022). Car independence in an automobile society? The everyday mobility practices of residents in a car-reduced housing development. Travel Behaviour and Society, 28, 90-105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2022.02.008

Valor, C., Martino, J., y Ruiz, L. (2023). Blends of emotions and innovation (Non)adoption: A focus on green energy innovations. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 48, 100759. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100759

FINANCING

The authors did not receive funding for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Ingrid Johana Salas.

Data curation: Natalia Helena Álvarez.

Formal analysis: Ingrid Johana Salas.

Fund acquisition: Not applicable.

Research: Ingrid Johana Salas.

Methodology: Ingrid Johana Salas and Natalia Helena Álvarez.

Project administration: Ingrid Johana Salas.

Resources: Ingrid Johana Salas.

Software: Ingrid Johana Salas.

Supervision: Natalia Helena Álvarez.

Validation: Natalia Helena Álvarez.

Visualization: Ingrid Johana Salas and Natalia Helena Álvarez.

Writing - original draft: Ingrid Johana Salas.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Natalia Helena Álvarez.