Scientific and Technological Research Article

Institutional factors that impact the entrepreneurial activity of university students

Factores institucionales que impactan en la actividad emprendedora de los estudiantes universitarios

Oscar Mauricio Gómez

Miranda1 ![]() *

*

ABSTRACT

Higher education institutions (HEIs) have a responsibility towards the comprehensive transformation, both social and economic, that they bring to individuals through their access to teaching and learning processes. Therefore, through a document review methodology, the aim was to identify the main institutional factors that impact students' entrepreneurial activity. In this way, a unified input is generated to support the programs and initiatives of each institution, to contribute to their strengthening and the promotion of entrepreneurial activity. It was found that entrepreneurship education should be approached as something other than the ultimate goal but as an expected outcome of a comprehensive education, fostering the development of essential life skills such as creativity and innovation.

Keywords: entrepreneurship, students, entrepreneurship programs, university, business creation.

JEL Classification: L22, L26, M13, M53

RESUMEN

Las instituciones de educación superior (IES) tienen una responsabilidad ante la transformación integral, social y económica que genera en las personas, por medio de su acceso a los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Por lo que, desde una metodología de revisión documental, se buscó identificar los principales factores institucionales que impactan en la actividad emprendedora de los estudiantes. De esta forma, se genera un insumo unificado que sirva para los programas e iniciativas de cada institución, con el fin de aportar a su fortalecimiento e incentivo de la actividad emprendedora. Se encontró que la formación en emprendimiento no debe ser abordada como el fin máximo, sino como un resultado esperado de una educación integral, hacia el desarrollo de habilidades necesarias para la vida, como la creatividad y la innovación.

Palabras claves: creación de empresa, estudiantes, programas de emprendimiento, universidad.

Clasificación JEL: L22, L26, M13, M5

Received: 15-09-2022 Revised: 19-11-2022 Accepted: 15-12-2022 Published: 13-01-2023

Editor:

Carlos Alberto Gómez Cano ![]()

1 Corporación Unificada Nacional de Educación Superior. Bogotá, Colombia.

Cite as: Gómez, O. (2023). Factores institucionales que impactan en la actividad emprendedora de los estudiantes universitarios. Región Científica, 2(1), 202327. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202327

INTRODUCTION

Entrepreneurship, understood at the market level as the possibility of generating and implementing a sustainable and ethical business model, is fundamental in the current context (Lüdeke-Freund, 2020). It emerges in a context marked by the neoliberal model, not only from the economy but also from state policies, which implies the increase of possibilities and wealth of social groups that seek to take advantage of opportunities to improve the living conditions of populations that have less access to financial, social and cultural capitals (Wu & Si, 2018).

In Schumpeter's classic work (1942), the entrepreneur is referred to as a person who acts as an undertaking, so he is defined as a dynamic and exceptional individual, creator, and even innovator. In this sense, different research has evidenced the benefits of entrepreneurship in individual development and the enhancement of human growth (Nisula et al., 2017), as it improves its creative dimensions as a leader (Kaptein, 2019), as a generator of solutions (Ballor & Claar, 2019) and as a way to increase economic capital (Stoica et al., 2020).

Linked to this definition, the national regulatory framework of Law 1014 of 2006 conceives the entrepreneur as "a person with the capacity to innovate; understood as the capacity to generate goods and services in a creative, methodical, ethical, responsible and effective way (Congress of the Republic of Colombia, 2006, Art. 1). In this sense, entrepreneurship is approached from the legal framework of the country as:

A way of thinking and acting oriented towards wealth creation. It is a way of thinking, reasoning, and acting focused on opportunities, approached with a global vision, and carried out through leadership and balanced and calculated risk management; its result is the creation of value that benefits the company, the economy, and society. [Una manera de pensar y actuar orientada hacia la creación de riqueza. Es una forma de pensar, razonar y actuar centrada en las oportunidades, planteada con visión global y llevada a cabo mediante un liderazgo, equilibrado y la gestión de riesgo calculado, su resultado es la creación de valor que beneficia a la empresa, la economía y la sociedad.]

Thus, in a paradigm of little or no intervention in the economy and in the social sphere, where the market and its dynamics are determining actors, the inhabitants of the so-called "developing countries" or "efficiency-driven economies" (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor - GEM, 2017), must seek alternatives to generate wealth and jobs. In this horizon, entrepreneurship is consolidated as an alternative, not only for personal economic development but also for regional and national development, through the generation of jobs, the dynamization of services and products, and innovation, this being an essential part of competitiveness in a country (Porter, 1992).

Entrepreneurship, as a topic of interest, has taken an extraordinary boom in Colombia since the 2000s; this, if we take as a milestone the creation of Law 1014 of 2006, promoting the culture of entrepreneurship and, likewise, the enactment of Law 2069 of December 31, 2020, through which entrepreneurship is promoted in Colombia (Fuentes, 2021). However, it is a regulated and worked area in the country and presents a current relevance that has driven research interest globally (Sánchez et al., 2017).

This situation arises from the search, on the part of different countries, to promote more developed entrepreneurial ecosystems that generate favorable contexts for the creation of new companies, which in turn has an impact on stimulating innovation and business productivity (Van Praag & Versloot, 2007). These economies are classified by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, 2021) as "innovation-driven economies," understanding that entrepreneurship has been the basis of today's world powers.

In this sense, a region's economic and social development is directly related to the quantity and quality of the existing business system (Stoica et al., 2020). This is because it contributes to the promotion of innovation, which, in turn, fosters competitiveness and poverty reduction through the supply of employment, as well as the possibility of generating new options anchored to the life project (Bucardo et al., 2015); a situation that, moreover, has generated mobility of governments to promote and strengthen entrepreneurship in the countries.

However, not all the responsibility for stimulating the creation of companies falls on governments, but also on society and educational institutions, which are committed to fostering an entrepreneurial culture that has an impact on all levels of the individual's life (Jansen et al., 2015), which is why it is necessary to investigate strategies to improve entrepreneurship training in an interdisciplinary manner (Toca, 2010).

Thus, the university becomes a relevant actor in the planning and execution of entrepreneurship training scenarios through programs and curricula that facilitate and prioritize the development of transversal competencies (Vélez et al., 2020), not only for business creation but in an integral way so that education contributes to the development of a life project with the ability to transform the social, economic and cultural conditions of people (Bravo et al., 2021).

Educational centers and academia have established themselves as relevant actors within the entrepreneurial ecosystem and as a stimulus for the generation of new businesses (Sánchez et al., 2017). For this reason, some research precedents developed by educational institutions on their students and their praxis should be considered to stimulate entrepreneurial activity at the academic and institutional levels (Gómez & Sánchez, 2022).

Most of the research conducted from and for the analysis of academia about entrepreneurship has focused on the characterization of the entrepreneur, such as the proposal made by Acosta et al. (2014) for the Latin American case and based on the GEM model. Proposals of this type respond to the need to understand the conditions for entrepreneurship in this region, characterized by heterogeneity in the economic, social, and political developments of the countries that comprise it.

Similarly, the Colombian Association of Faculties of Administration - ASCOLFA (2017) published the Student Entrepreneurial Profile of the Faculties of Administration, attached to the Eastern Chapter of ASCOLFA. It includes the processes developed by public and private educational institutions in this country's sector regarding entrepreneurship, its promotion and execution among students, and the characterization of the university entrepreneur, especially in Santander and Norte de Santander.

For this inquiry, the aptitudes and attitudes of the students were taken as variables, such as initiative, strength in the face of skills, capacity to assume risks, flexibility, learning capacity, organization and planning of time and work, self-confidence, eagerness for achievement, the vision of the company-business, perception of the social environment and the entrepreneurial process, as well as the vision of the mechanisms and social and cultural norms that motivate entrepreneurship (ASCOLFA, 2017).

For its part, the Universidad Industrial de Santander (UIS) conducted a similar exercise, which aimed to "identify the entrepreneurial profile of UIS students in order to design training plans in entrepreneurship, according to the needs identified as a result of this study" (Pedraza et al., 2015, p. 141), thus showing the relevance of each institution to have a diagnosis of the entrepreneurial activity of its students. For this case, the authors considered aspects related to gender, entrepreneurial intention, risk aversion, references of family members with entrepreneurship, and the business idea's innovation level.

Therefore, universities have started from the characterization of their students, both entrepreneurs, and non-entrepreneurs, to have a baseline that allows them to structure their institutional policies and guidelines to promote and strengthen a culture of business creation. Thus, after the first phase of characterization, it is necessary - for any educational center - to identify the institutional success factors that impact the entrepreneurial activity of university students. For this reason, this document sought to delve into documented cases to present, summarize, and expose these essential elements, which each institution can analyze and adapt.

METHODS

This article has a documentary review approach based on the analysis of case studies of higher education institutions. Therefore, it comprises a qualitative, descriptive approach. Thus, the objective is to identify the main institutional factors that impact the entrepreneurial activity of university students.

In order to achieve, develop, and fulfill the proposed objective, the research process was structured in two phases. The first phase involves the review and theoretical conceptualization of the term "entrepreneurship," its impact in the regions of influence, and the development of the promotion of business creation in higher education institutions. This exploration provides the basis for the work, which includes a review in databases and indexed academic journals, such as Google Scholar, Scopus, Science Direct, and Dialnet.

On the other hand, the second phase addresses analyzing systematized cases by higher education institutions to identify successful strategies and practices, such as entrepreneurship programs or innovation centers, to increase their knowledge and promote their experiences in addressing the topic. This is intended to achieve the proposed objective by presenting the results, conclusions, and recommendations.

RESULTS

Seven general categories can be found to approach the factors that stimulate entrepreneurship: 1) sociodemographic attributes, which include variables such as age, gender, access and scope of an educational system, and income available to the family unit (Chafloque-Cespedes et al., 2021); 2) attitudes towards entrepreneurship, which can be observed from perception, especially fear, opportunity generation, and risk, as well as interest in entrepreneurship, creativity, achievement orientation, and flexibility (Mahfud et al., 2020); 3) the level of development of entrepreneurial activity in a region (Maiza et al., 2020) is due to the importance of the facilities and opportunities to create a business.

Similarly, there are 4) the motivational factors that affect the aspirations and impacts of entrepreneurial activity (Poblete et al., 2019), such as employment generation, innovation, offering a product or service to satisfy the population, and the development of a life project; 5) the existence of family factors, such as previous entrepreneurial activity in the close nucleus and the guidance it can offer (Molina, 2020); 6) legal and tax factors that stimulate or hinder an entrepreneurial system (Ardagna & Lusardi, 2010); and, finally 7) institutional favors from academia that encourage training, as well as the generation of business ideas (Díaz-Casero et al., 2012).

However, the academy has a direct relationship with the company and its creation, from one of its roles as a critical trainer for the productive system by stimulating independence or from training for the labor market (Rayevnyeva et al., 2018). Thus, by understanding the importance of the entrepreneurial phenomenon and the impact it can have multidimensionally and at various scales, training processes on the knowledge and skills required for generating and implementing a solid business idea become of particular interest (Martin et al., 2013).

Regarding training, State of the Art of Teaching Entrepreneurship (Castillo, 1999) is essential and pioneering in the field since it provides a historical overview of the existing models for teaching and learning processes in entrepreneurship. This aspect also generates a series of recommendations, such as the cross-cutting promotion of entrepreneurship in all subjects "as a way of thinking and acting" (p. 14). Therefore, entrepreneurship is not only related to creating a company but to a philosophy of life anchored to risk management and the search for opportunities that benefit the individual and society, which can be encouraged by teachers and educational institutions.

To create a culture of entrepreneurship in the academic sphere, one should start with the institutional factors that affect it (Farny et al., 2013). In this regard, some leading traditional initiatives have been articulated toward creating undergraduate and graduate programs to support entrepreneurship, especially from specializations and master's degrees (Kirkwood et al., 2014). However, authors such as Issa and Tesfaye (2020) argue that it is okay to establish a curricular program strictly focused on entrepreneurship since the transversality of topics can be anchored to any career. Thus, specific actions strengthen and encourage entrepreneurial activity, such as business creation chairs, planning and developing business fairs, structuring business plans, and even offering personalized counseling benefits (Lüthje & Franke, 2002).

In contrast to this institutional approach, Jansen et al. (2015) propose a model for promoting entrepreneurship based on education and developing transversal life skills. This would require the creation of work environments that simulate a controlled scenario for the development of ideas and, from the incubation of these, consolidate learning tools (Meister & Mauer, 2019). Thus, a chair in business creation should be thought of from the point of view of comprehensiveness and the development of competencies beyond developing a business plan.

Under this logic, aligned with Issa and Tesfaye (2020), the formation and implementation of chairs in entrepreneurship, although a necessary process, is not enough to generate an entrepreneurial intention; instead, it should be linked to a teaching approach that stimulates the development of lateral and disruptive thinking skills in students (Lautenschläger & Haase, 2011), such as project-based or problem-based learning, whose objective is the search for opportunities and creativity. Similarly, it is advisable to have mechanisms for the student to demonstrate the possible financial and administrative feasibility of the idea as factors that have a positive impact on motivation, favoring the entrepreneurial spirit and its decision against traditional employment or independence (Vélez et al., 2020).

In addition, students should receive an education in entrepreneurship from the first academic semester since the constant proximity generates an atmosphere of familiarity and increases the possibility of exploration in the different stages of the student's passage through the institution (Pacheco-Ruiz et al., 2022), so that the entrepreneurship chair can be structured from different levels of training, according to their degree of depth and specialization.

Likewise, from the entrepreneurship chairs, as from the alternative programs where students show interest in the subject, it is advisable to encourage teamwork from a multidisciplinary approach, which helps to offer a different but integrative and complementary look at the ideas (Jansen et al., 2015; Castillo-Vergara et al., 2018). Seen in this way, this approach presents the challenge of resistance to collaboration with external groups or individuals, which must be accompanied by trust-stimulating integrative activities by facilitating the knowledge and skills of the other participants.

The chair or programs for business creation should address legal, tax, and regulatory approaches, which help to understand the functioning of the economic system with its environment, from its rights and obligations, as well as from the development of adaptation to meet changing requirements, thus allowing an approach to the real sector and its conditions (Vargas & Uttermann, 2020).

Similarly, the programs should be voluntary and not mandatory as they seek to stimulate a taste and potentiate the entrepreneurial spirit, reflected in academic performance and their application in a natural environment (Castillo-Vergara et al., 2018). Therefore, autonomy and flexibility for the student should be prioritized. Regarding this, and the institution seeks an entrepreneurial and transversal approach for all programs, alternatives that motivate the student should be offered beyond the compulsory nature of the professorship.

On the other hand, the teaching and development of a business plan should not be the only focus; it is also essential that students can generate and develop a work experience through internships or alternation between work and study in order to obtain an impression of the natural functioning of the market and organizations. A knowledge that, among other things, allows them to develop valuable skills in business development, the functioning of processes, and the relationship between organizations and their environment; factors that facilitate the reality with the creation and management of the company (Bravo et al., 2021).

In this context, the traditional and focused look inside the academy - as a training path - should be complemented by greater openness and relationship with the environment, where the research results transfer offices (TTOs) and technological product incubators appear (Macias et al., 2018; Meister & Mauer, 2019). These options articulate the interests of society, business, and the education sector to create companies and developments with a genuine interest and application in the market or solutions to community problems (de Lucio et al., 2000). Ultimately, they seek a transformation from the theoretical to the practical.

Additionally, both TTOs and incubators offer the possibility of testing innovative ideas before they reach the market using a technical and financial feasibility analysis of the business projects (De Wit-de Vries et al., 2019). This possibility encourages pitches and prototyping not to be developed at a primary or only ideation level but to offer a preview of the production process of the complete product in order to motivate the student with it in front of the generated results.

Similarly, regarding the external approach, a recommended strategy is to attract and share the experiences of successful entrepreneurs who can socialize their cases (Ibraheem et al., 2011). Likewise, it is vital to create spaces to facilitate networking and access to internal and external financing mechanisms, such as creating a crowdfunding platform, which can serve as a collective financing method and attract investors (Kraus et al., 2016).

However, any action designed to stimulate the creation of companies should be based on the maxim of responsible production and marketing at the economic, social, and environmental levels (Ma & Bu, 2021). In this order, ethical behavior, from the first levels of training, should be a characteristic that has an impact on the culture of entrepreneurs, not only for the maintenance of a corporate image or the search for competitiveness and differentiation strategies but as a sense of commitment and will, before the actions of the company.

Such a change can start with training, first with teachers, inviting them to reflect on the critical competencies for entrepreneurship and non-dependence on a business plan (Velasco et al., 2019). Thus, to achieve a change of perspective towards a sustainable model, teachers must first appropriate the tools and knowledge that seek a balance between the interests of social actors, the search for profitability, and the consumption of resources.

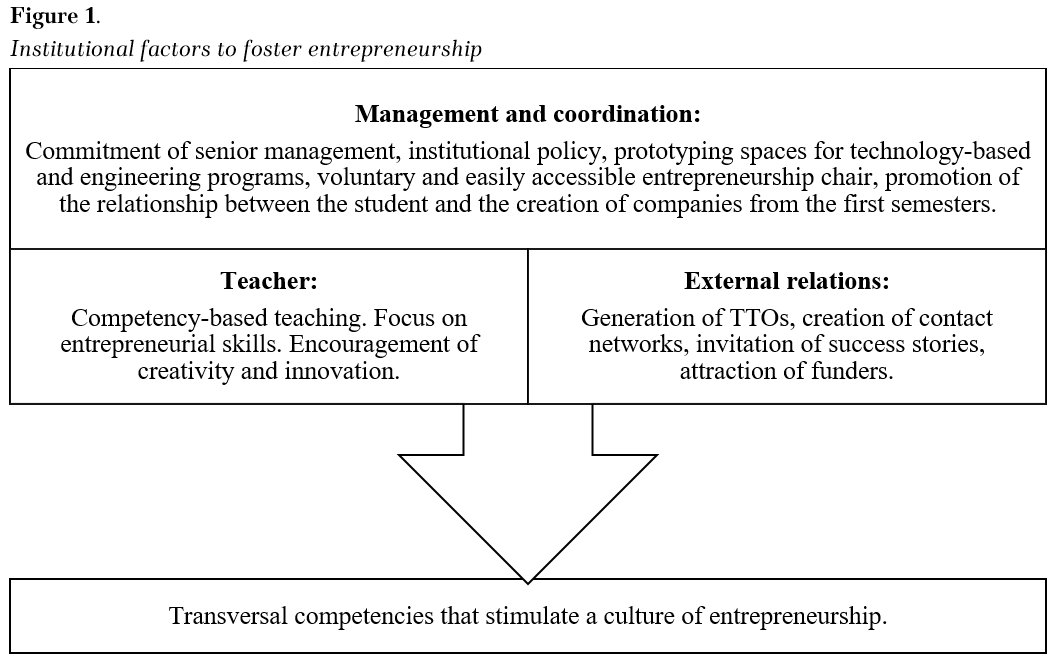

According to the above, a commitment from the top management in educational institutions is required, which is reflected in the existence of a policy that guides entrepreneurship (Vásquez, 2017) in order to administratively, technologically, and financially support the processes and that allows at the same time to communicate guidelines and directives that stimulate the scenarios conducive to business creation. These key factors to be stimulated are summarized below in figure 1:

Source. Own elaboration

CONCLUSIONS

Countries find economic and social growth possible in entrepreneurship; under this premise and in favor of their progress, they demand the collaboration of all actors. Among them, the role of Higher Education Institutions is relevant since they aim to train individuals who will enter the productive sector, both from the perspective of employees and generators of employment. It is through this scenario that education must be projected from an actual application, which has an impact on the transformation of society beyond its theoretical meaning. It is, therefore, a context that invites us to reflect on the relevance of entrepreneurship courses, focused on the establishment of a necessary business plan, but which prioritizes qualification, leaving in the background the fact of taking it to applicability, as well as the development of skills that can be useful for the student, in a work and even personal context.

Meanwhile, a chair in entrepreneurship, optional and accessible to all academic programs, is only a first step towards generating a culture that encourages students to become more involved in creating enterprises. However, its content should not offer an education aimed at stimulating the creation of a company in people but rather to develop transversal skills that will lead to a culture conducive to entrepreneurship as a philosophy of life.

Therefore, the HEIs can take the responsibility of offering an education for the generation of a transforming life project, where the option of creating a company is found as a path towards the integral improvement of the student and the community at an economic and social level where the emergence of the entrepreneurial university should not be seen as a culturalized cloister towards the creation of a company, but as an environment that stimulates the development of skills necessary for entrepreneurship, such as risk management, innovation, the search for opportunities and creativity.

In this sense, institutional factors can be approached from the managerial commitment, the actions of students, and the mechanisms of relationship with the environment. These factors, which must be adapted to each educational reality, affect entrepreneurship training so that their appropriation can shape the perception of students in schools about creating a business as a life option.

Finally, and by what has been said so far, to bring about a transformative change that stimulates students' interest in entrepreneurship, more is needed to restructure the primary approach of entrepreneurship subjects, characterized by their anchoring to developing a business guide. It is also necessary to promote an institutional change in the educational model, which stimulates the development of transversal skills for life and is helpful for entrepreneurship in all the academic programs offered.

REFERENCES

Acosta, C., Zárate, A. e Ibarra, M. (2014). Caracterización del emprendedor latinoamericano, a partir del modelo Global Entrepreneurship Monitor–GEM. Revista Económicas CUC, 35 (1), 135-155. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5085560

Ardagna, S. y Lusardi, A. (2010). Heterogeneity in the effect of regulation on entrepreneurship and entry size. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(2-3), 594-605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00529.x

ASCOLFA. (2017). Perfil Emprendedor del Estudiante de las Facultades de Administración adscritas al Capítulo Oriente de ASCOLFA. Editorial Mejoras. https://bonga.unisimon.edu.co/handle/20.500.12442/6558

Ballor, J. y Claar, V. (2019). Creativity, innovation, and the historicity of entrepreneurship. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 8(4), 513-522. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEPP-03-2019-0016

Bravo, I., Bravo, M., Preciado, J., y Mendoza, M. (2021). Educación para el emprendimiento y la intención de emprender. Revista Economía y Política, 33, 139-155. http://scielo.senescyt.gob.ec/scielo.php?pid=S2477-90752021000200139&script=sci_arttext

Bucardo, C., Saavedra, G. y Camarena, A. (2015). Hacia una comprensión de los conceptos de emprendedores y empresarios. Suma de Negocios, 6(13), 98-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sumneg.2015.08.009

Castillo, A. (1999). Estado del arte de la enseñanza en emprendimiento. INTEC, Chile.

Castillo-Vergara, M., Álvarez-Marín, A., Alfaro-Castillo, M., Henríquez, J. y Quezada, I. (2018). Factores clave en el desarrollo de la capacidad emprendedora de estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Métodos Cuantitativos para la Economía y la Empresa, 25, 111-129. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/195401

Chafloque-Cespedes, R., Alvarez-Risco, A., Robayo-Acuña, P.-V., Gamarra-Chavez, C.-A., Martinez-Toro, G.-M. y Vicente-Ramos, W. (2021). Effect of Sociodemographic Factors in Entrepreneurial Orientation and Entrepreneurial Intention in University Students of Latin American Business Schools. Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research, 11, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 151-165. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2040-724620210000011010

Congreso de la República de Colombia. (27 de enero de 2006). Ley de fomento a la cultura del emprendimiento. [Ley No. 1014] do: 46.164. http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/ley_1014_2006.html

de Lucio, I., Martínez, E., Cegarra, F. y Gracia, A. (2000). Las relaciones universidad-empresa: entre la transferencia de resultados y el aprendizaje regional. Espacios, 21(2), 127-148. https://www.revistaespacios.com/a00v21n02/61002102.html

De Wit-de Vries, E., Dolfsma, W., van der Windt, H. y Gerkema, M. (2019). Knowledge transfer in university–industry research partnerships: a review. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(4), 1236-1255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9660-x

Díaz-Casero, J., Ferreira, M., Hernández, R., y Barata, L. (2012). Influence of institutional environment on entrepreneurial intention: a comparative study of two countries university students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(1), 55-74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0134-3

Farny, S., Frederiksen, S., Hannibal, M. y Jones, S. (2016). A Culture of entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28(7-8), 514-535. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1221228

Fuentes, M. (2021). Los marcos de restructuración preventiva: una solución a la crisis de empresa ya la declaración de insolvencia. Inciso, 23(2), 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.18634/incj.23v.2i.1156

GEM Colombia. (2017). Actividad empresarial colombiana. https://gemcolombia.org/

Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (2021). Informe global. https://www.gemconsortium.org/reports/latest-global-report

Gómez-Miranda, O. y Sánchez-Castillo, V. (2022). The triple helix as a dynamic system for the generation of innovative capacities in MIPYMES. Revista Gestión y Desarrollo Libre, 7(14), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.18041/2539-3669/gestionlibre.14.2022.10699

Gonzaga, A. y Alaña, C. (2017). Competitividad y emprendimiento: herramientas de crecimiento económico de un país. INNOVA Research Journal, 2(8.1), 322-328. https://doi.org/10.33890/innova.v2.n8.1.2017.386

Haase, H., y Lautenschläger, A. (2011). The ‘teachability dilemma’of entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 145-162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-010-0150-3

Ibraheem, D. y Aijaz, N. (2011). Dynamics of Peer Assisted Learning and Teaching at an entrepreneurial university: an experience to share. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(12), 93-99. https://acortar.link/vojnmp

Issa, E., y Tesfaye, Z. (2020). Entrepreneurial intent among prospective graduates of higher education institution: an exploratory investigation in Kafa, Sheka, and Bench-Maji Zones, SNNPR, Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-020-00137-1

Jansen, S., Van De Zande, T., Brinkkemper, S., Stam, E. y Varma, V. (2015). How education, stimulation, and incubation encourage student entrepreneurship: Observations from MIT, IIIT, and Utrecht University. The International Journal of Management Education, 13(2), 170-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2015.03.001

Kaptein, M. (2019). The moral entrepreneur: A new component of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(4), 1135-1150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3641-0

Kirkwood, J., Dwyer, K. y Gray, B. (2014). Students' reflections on the value of an entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 12(3), 307-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.07.005

Kraus, S., Richter, C., Brem, A., Cheng, C., y Chang, M. (2016). Strategies for reward-based crowdfunding campaigns. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 1(1), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.01.010

Lüdeke‐Freund, F. (2020). Sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and business models: Integrative framework and propositions for future research. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(2), 665-681. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2396

Ma, Z. y Bu, M. (2021). A new research horizon for mass entrepreneurship policy and Chinese firms’ CSR: introduction to the thematic symposium. Journal of Business Ethics, 169(4), 603-607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04549-7

Macias, U., Valencia, A. y Montoya, R. (2018). Factores implicados en la transferencia de resultados de investigación en las instituciones de educación superior. Ingeniare. Revista Chilena de Ingeniería, 26(3), 528-540. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-33052018000300528

Mahfud, T., Triyono, M., Sudira, P., y Mulyani, Y. (2020). The influence of social capital and entrepreneurial attitude orientation on entrepreneurial intentions: the mediating role of psychological capital. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 26(1), 33-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2019.12.005

Maiza, C., Rivera, L. y Morales, U. (2020). El fracaso de la actividad emprendedora en el contexto latinoamericano. Revista UNIANDES Episteme, 7(2), 162-176. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8298146

Martin, B., McNally, J. y Kay, M. (2013). Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 211-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.03.002

Meister, A. y Mauer, R. (2019). Understanding refugee entrepreneurship incubation – an embeddedness perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(5), 1065-1092. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2018-0108

Molina, J. (2020). Family and entrepreneurship: New empirical and theoretical results. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(1), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09667-y

Nisula, A., Olander, H. y Henttonen, K. (2017). Entrepreneurial motivations as drivers of expert creativity. International Journal of Innovation Management, 21(05), 174005. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919617400059

Pacheco-Ruiz, C., Rojas-Martínez, C., Niebles-Nuñez, W., y Hernández-Palma, H. (2022). Caracterización del emprendimiento desde un enfoque universitario. Formación universitaria, 15(1), 135-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062022000100135

Pedraza, A. Ortiz, C. y Pérez, S. (2015). Perfil emprendedor del estudiante de la Universidad Industrial de Santander. Revista Educación en Ingeniería, 10 (19), 141-150. https://educacioneningenieria.org/index.php/edi/article/viewFile/550/244

Poblete, C., Sena, V., y Fernández de Arroyabe, J. (2019). How do motivational factors influence entrepreneurs’ perception of business opportunities in different stages of entrepreneurship? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(2), 179-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1564280

Porter, M. (1992). La ventaja competitiva de las naciones. Rio de Janeiro: Campus.

Rayevnyeva, O., Aksonova, I. y Ostapenko, V. (2018). Formation interaction and adaptive use of purposive forms of cooperation of university and enterprise structures. Innovative Marketing, 14(3), 44. http://dx.doi.org/10.21511/im.14(3).2018.05

Sánchez, J., Ward, A., Hernández, B., y Flórez, J. (2017). Educación emprendedora: Estado del arte. Propósitos y Representaciones, 5(2), 401-473. http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2017.v5n2.190

Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalismo, socialismo y democracia. Madrid: Aguilar.

Stoica, O., Roman, A. y Rusu, V. (2020). The nexus between entrepreneurship and economic growth: A comparative analysis on groups of countries. Sustainability, 12(3), 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031186

Toca, T. (2010). Consideraciones para la formación en emprendimiento: explorando nuevos ámbitos y posibilidades. Estudios Gerenciales, 26(117), 41-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0123-5923(10)70133-9

Van Praag, C. y Versloot, P. (2007). What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Business Economics, 29(4), 351-382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9074-x

Vargas, V. y Uttermann, G. (2020). Emprendimiento: factores esenciales para su constitución. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 25(90), 709-720. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=29063559024

Vásquez, C. (2017). Educación para el emprendimiento en la universidad. Estudios de la Gestión: Revista Internacional de Administración, 2, 121-147. https://doi.org/10.32719/25506641.2017.2.5

Velasco, C., Estrada, I., Pabón, M., y Tójar, C. (2019). Evaluar y promover las competencias para el emprendimiento social en las asignaturas universitarias. REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 131, 199-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/REVE.63561

Vélez, C., Bustamante, M., Loor, B. y Afcha, S. (2020). La educación para el emprendimiento como predictor de una intención emprendedora de estudiantes universitarios. Formación Universitaria, 13(2), 63-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062020000200063

Wu, J. y Si, S. (2018). Poverty reduction through entrepreneurship: Incentives, social networks, and sustainability. Asian Business & Management, 17(4), 243-259. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-018-0039-5

FINANCING

No external financing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (ORIGINAL VERSION SPANISH)

Se agradece a la Corporación Unificada Nacional de Educación Superior (CUN) por el apoyo recibido para el desarrollo de la investigación.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Oscar Mauricio Gómez Miranda.

Formal analysis: Oscar Mauricio Gómez Miranda.

Research: Oscar Mauricio Gómez Miranda.

Methodology: Oscar Mauricio Gómez Miranda.

Validation: Oscar Mauricio Gómez Miranda.

Writing - original draft: Oscar Mauricio Gómez Miranda.

Writing - revision and editing: Oscar Mauricio Gómez Miranda.